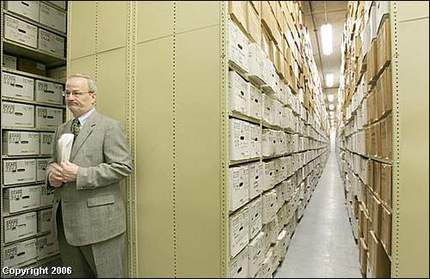

Indian records buried in a limestone cave near Lenexa, Kansas. The Omaha-World Herald identifies the unhappy gentleman as "Ross Swimmer, a special assistant with the Interieor Department" (see source cited for excerpt below). The Olympian Online of Olympia, Washington identifies him as "John Allshouse, assistant regional administrator for the National Archives" (see source cited for image). Source of image: http://159.54.227.3/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060507/NEWS/60507029

Indian records buried in a limestone cave near Lenexa, Kansas. The Omaha-World Herald identifies the unhappy gentleman as "Ross Swimmer, a special assistant with the Interieor Department" (see source cited for excerpt below). The Olympian Online of Olympia, Washington identifies him as "John Allshouse, assistant regional administrator for the National Archives" (see source cited for image). Source of image: http://159.54.227.3/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20060507/NEWS/60507029

LENEXA, Kan. (AP) – Seventy feet beneath the prairie, the government is filling limestone caverns – protected by guards and a bomb-sniffing dog – with truckloads of American Indians’ financial and cultural records.

What is ground zero for an accounting that will take seven years and cost $335 million owes its existence to a bitter class-action lawsuit brought against the Interior Department a decade ago. Still, it’s only a short version of the historical accounting that Indians demanded but no longer want, because they do not think it can be done properly.

The Indians say the government mismanaged a trust in their names for 120 years and now owes them tens of billions of dollars.

. . .

Concerns about the how the trust accounts are managed are almost as old as the trust itself.

In 1915, the Joint Commission of Congress on Indian Funds warned of "fraud, corruption and institutional incompetence almost beyond the possibility of comprehension." In 1928, the Interior Department found Indian trust data unreliable and almost useless. Dozens of other scathing reports followed.

Finally, in 1994, Congress demanded that the department fulfill an obligation to account for money received and disbursed. A year later when account statements still had not been reconciled, Elouise Cobell of the Blackfeet Indian tribe in Montana joined with the Boulder, Colo.-based Native American Rights Fund and others in suing.

"Fractionalization" of accounts is a major obstacle in managing the trust. As ownership of the 160-acre and smaller land parcels transferred from generation to generation, proceeds from the trust accounts had to be divided among more and more descendants. Department officials say 90 percent of the transactions are for less than $100.

"In every category it has cost us more to find the errors than the total amount of the errors we found," said departing Interior Secretary Gale Norton. "When you consider that we have millions of transactions under $1, you’re spending $3,500 to find out if we handled $1 correctly."

For the full story see:

"Paper Trail Fills Massive Cave." Omaha World-Herald (Sun., May 21, 2006): 10A.

(Note, the online version, has a different title and a day-earlier publication date:

"Counting Up What Indians Are Owed." Omaha World-Hearald (Sat., May 20, 2006).)

The man in the photo is not Ross Swimmer.