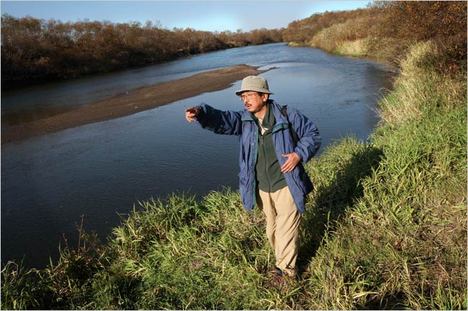

“Luis H. Rodriguez, an I.B.M. executive, with his children, Alec, 5, and Evia, 2, often works from his home or on the road.” Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Luis H. Rodriguez, an I.B.M. executive, with his children, Alec, 5, and Evia, 2, often works from his home or on the road.” Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Daniel Pink in his Free Agent Nation argued that a growing number of American workers would want the control, challenge and freedom of working for themselves as entrepreneurs, or “free agents.” To attract workers who have the option of being free agents, it is plausible that employers increasingly will have to offer jobs that provide workers with greater autonomy. The article quoted below, suggests that this may in fact be happening, at least in information technology firms.

(p. A1) SOMERS, N.Y. — It’s every worker’s dream: take as much vacation time as you want, on short notice, and don’t worry about your boss calling you on it. Cut out early, make it a long weekend, string two weeks together — as you like. No need to call in sick on a Friday so you can disappear for a fishing trip. Just go; nobody’s keeping track.

That is essentially what goes on at I.B.M., one of the cornerstones of corporate America, where each of the 355,000 workers is entitled to three or more weeks of vacation. The company does not keep track of who takes how much time or when, does not dole out choice vacation times by seniority and does not let people carry days off from year to year.

Instead, for the past few years, employees at all levels have made informal arrangements with their direct supervisors, guided mainly by their ability to get their work done on time. Many people post their vacation plans on electronic calendars that colleagues can view online, and they leave word about how they can be reached in a pinch.

“It’s like when you went to college and you didn’t have high school teachers nagging you anymore,” said Mark L. Hanny, I.B.M.’s vice president of independent software vendor alliances. “Employees like that we put more accountability on them.”

. . .

(p. 18) Aided by broadband connections, cellphones and video conferencing software, 40 percent of I.B.M.’s employees have no dedicated offices, working instead at home, at a client’s site, or at one of the company’s hundreds of “e-mobility centers” around the world, where workers drop in to use phones, Internet connections and other resources.

. . .

Luis H. Rodriguez, the director of market management in I.B.M.’s software group, said he visits his office here in Somers about once a week, working the rest of the time on the road or at his home in Ridgefield, Conn., where he sat one recent afternoon at the kitchen table with his laptop open.

He said that in six years at I.B.M. he can recall only one time when he asked a co-worker not to take a long weekend off — when their group was about to buy another company — and that calling colleagues or checking e-mail while visiting relatives in Texas or Illinois is a fair trade for being able to work from home so he can spend more time with his children, Alec, 5, and Evia, 2.

. . .

“If you look at the organizations that have done more radical things, they tend to be technology companies with salaried people,” where flexibility in job performance “is embedded into the culture of the place,” noted Max Caldwell, a managing principal in the work force effectiveness area at Towers Perrin, a human resources consultant.

Indeed, I.B.M.’s Mr. Calo said that the flexibility has helped the company compete with the more freewheeling atmosphere at start-up rivals in the technology world that have lured away some of its talent over the years.

For the full story, see:

KEN BELSON. “At I.B.M., a Vacation Anytime, Or Maybe No Vacation at All.” The New York Times (Fri., August 31, 2007): A1 & A18.

(Note: ellipses added.)

The reference for the Pink book, is:

Pink, Daniel H. Free Agent Nation: How America’s New Independent Workers Are Transforming the Way We Live. New York: Warner Business Books, 2001.

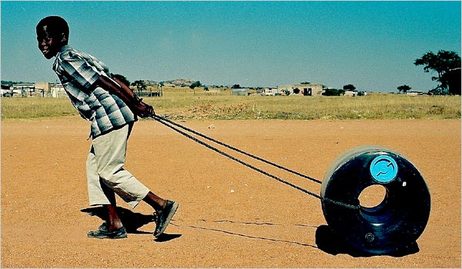

Moving water is easier with the 20-gallon rolling drum. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Moving water is easier with the 20-gallon rolling drum. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

"A device that U.P.S. installed in the cockpit of one of its cargo planes to display traffic information." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

"A device that U.P.S. installed in the cockpit of one of its cargo planes to display traffic information." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

"The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, dedicated to caring for the widowed, the orphaned and the needy, is in a “state of crisis.”" Source of the photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

"The Independent Order of Odd Fellows, dedicated to caring for the widowed, the orphaned and the needy, is in a “state of crisis.”" Source of the photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.