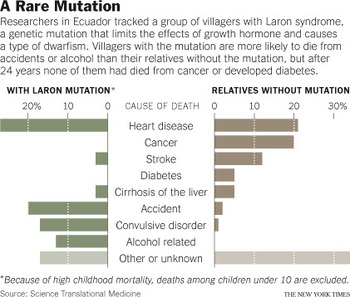

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. A6) People living in remote villages in Ecuador have a mutation that some biologists say may throw light on human longevity and ways to increase it.

The villagers are very small, generally less than three and a half feet tall, and have a rare condition known as Laron syndrome or Laron-type dwarfism. They are probably the descendants of conversos, Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal who were forced to convert to Christianity in the 1490s but were nonetheless persecuted in the Inquisition. They are also almost completely free of two age-related diseases, cancer and diabetes.

A group of 99 villagers with Laron syndrome has been studied for 24 years by Dr. Jaime Guevara-Aguirre, an Ecuadorean physician and diabetes specialist.

. . .

IGF-1 is part of an ancient signaling pathway that exists in the laboratory roundworm as well as in people. The gene that makes the receptor for IGF-1 in the roundworm is called DAF-2. And worms in which this gene is knocked out live twice as long as normal.

The Laron patients have the equivalent defect — their cells make very little IGF-1, so very little IGF-1 signaling takes place, just as in the DAF-2-ablated worms. So the Laron patients might be expected to live much longer.

Because of their striking freedom from cancer and diabetes, they probably could live much longer if they did not have a much higher than usual death rate from causes unrelated to age, like alcoholism and accidents.

. . .

A strain of mice bred by John Kopchick of Ohio University has a defect in the growth hormone receptor gene, just as do the Laron patients, and lives 40 percent longer than usual.

. . .

The longest-lived mouse on record is one studied by Dr. Bartke. It had a defect in its growth hormone receptor gene, just as do the Laron patients. “It missed its fifth birthday by a week,” he said. The mouse lived twice as long as usual and won Dr. Bartke a prize presented by the Methuselah Foundation (which rewards developments in life-extension therapies) in 2003.

For the full story, see:

NICHOLAS WADE. “Ecuadorean Villagers May Hold Secret to Longevity.” The New York Times (Thurs., February 17, 2011): A6.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated February 16, 2011 and has the title “Ecuadorean Villagers May Hold Secret to Longevity.”)

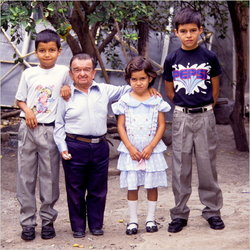

“A 67-year-old man who has Laron-type dwarfism with his daughter, 5, and sons, 7 and 10.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.