Artistic vision of germ-laden hand. (This is not the photographic image mentioned below, and used as a hospital screen-saver.) Source of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Artistic vision of germ-laden hand. (This is not the photographic image mentioned below, and used as a hospital screen-saver.) Source of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.

(p. 22) Leon Bender noticed something interesting: passengers who went ashore weren’t allowed to reboard the ship until they had some Purell squirted on their hands. The crew even dispensed Purell to passengers lined up at the buffet tables. Was it possible, Bender wondered, that a cruise ship was more diligent about killing germs than his own hospital?

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, where Bender has been practicing for 37 years, is in fact an excellent hospital. But even excellent hospitals often pass along bacterial infections, thereby sickening or even killing the very people they aim to heal. In its 2000 report “To Err Is Human,” the Institute of Medicine estimated that anywhere from 44,000 to 98,000 Americans die each year because of hospital errors — more deaths than from either motor-vehicle crashes or breast cancer — and that one of the leading errors was the spread of bacterial infections.

. . .

. . . the hospital needed to devise some kind of incentive scheme that would increase compliance without alienating its doctors. In the beginning, the administrators gently cajoled the doctors with e-mail, (p. 23) faxes and posters. But none of that seemed to work. (The hospital had enlisted a crew of nurses to surreptitiously report on the staff’s hand-washing.) “Then we started a campaign that really took the word to the physicians where they live, which is on the wards,” Silka recalls. “And, most importantly, in the physicians’ parking lot, which in L.A. is a big deal.”

For the next six weeks, Silka and roughly a dozen other senior personnel manned the parking-lot entrance, handing out bottles of Purell to the arriving doctors. They started a Hand Hygiene Safety Posse that roamed the wards and let it be known that this posse preferred using carrots to sticks: rather than searching for doctors who weren’t compliant, they’d try to “catch” a doctor who was washing up, giving him a $10 Starbucks card as reward. You might think that the highest earners in a hospital wouldn’t much care about a $10 incentive — “but none of them turned down the card,” Silka says.

When the nurse spies reported back the latest data, it was clear that the hospital’s efforts were working — but not nearly enough. Compliance had risen to about 80 percent from 65 percent, but the Joint Commission required 90 percent compliance.

These results were delivered to the hospital’s leadership by Rekha Murthy, the hospital’s epidemiologist, during a meeting of the Chief of Staff Advisory Committee. The committee’s roughly 20 members, mostly top doctors, were openly discouraged by Murthy’s report. Then, after they finished their lunch, Murthy handed each of them an agar plate — a sterile petri dish loaded with a spongy layer of agar. “I would love to culture your hand,” she told them.

They pressed their palms into the plates, and Murthy sent them to the lab to be cultured and photographed. The resulting images, Silka says, “were disgusting and striking, with gobs of colonies of bacteria.”

The administration then decided to harness the power of such a disgusting image. One photograph was made into a screen saver that haunted every computer in Cedars-Sinai. Whatever reasons the doctors may have had for not complying in the past, they vanished in the face of such vivid evidence. “With people who have been in practice 25 or 30 or 40 years, it’s hard to change their behavior,” Leon Bender says. “But when you present them with good data, they change their behavior very rapidly.” Some forms of data, of course, are more compelling than others, and in this case an image was worth 1,000 statistical tables. Hand-hygiene compliance shot up to nearly 100 percent and, according to the hospital, it has pretty much remained there ever since.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

The screen-saver at Cedars Sinai Hospital. Source of image: http://freakonomics.com/pdf/CedarsSinaiScreenSaver.jpg

The screen-saver at Cedars Sinai Hospital. Source of image: http://freakonomics.com/pdf/CedarsSinaiScreenSaver.jpg

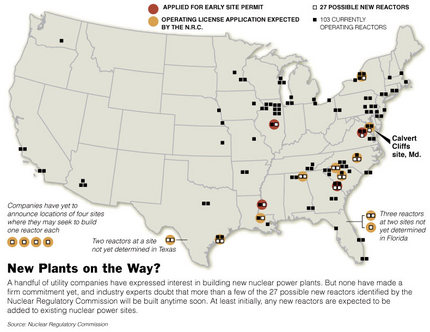

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.