“As Florida buys U.S. Sugar, company land could go on the block. The Fanjul family, with sugar operations like this one in Palm Beach County, is waiting.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“As Florida buys U.S. Sugar, company land could go on the block. The Fanjul family, with sugar operations like this one in Palm Beach County, is waiting.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Many years ago, CBS’s “Sixty Minutes” program ran a wonderful Steve Kroft piece (called, I think, “A Sweet Deal”) exposing how protectionist federal government sugar import quotas, benefit the extraordinarily wealthy and powerful Fanjul family, at the expense of ordinary consumers.

Nothing has changed:

(p. 1) IN June, Gov. Charlie Crist announced that Florida would buy one of the state’s two big sugar enterprises, the United States Sugar Corporation. He billed the purchase as a “jump-start” in the environmental restoration of the Everglades, which cane growers are accused of polluting with fertilizer runoff.

But in the end, the $1.7 billion buyout, scheduled to be completed in early 2009, may also prove to be a financial boon to the state’s remaining sugar superpower, Florida Crystals.

One of the country’s wealthiest families, the Fanjuls of Palm Beach, controls Florida Crystals and today touches virtually every aspect of the sugar trade in the United States.

. . .

“This is going to be a really good deal for the Fanjuls,” says Dexter Lehtinen, a former federal prosecutor whose 1988 lawsuit against the state led to a settlement instituting tough clean water standards. “The state embarked on a nonachievable goal, and now in desperation to wrap up some package, they’re going to have to give access to Florida Crystals on favorable terms.”

Others, like makers of candy and cereal, say the (p. 9) Fanjuls already control too much of the sugar trade. They want to buy sugar cheap and say the Fanjuls have long charmed Congress into legislating price supports that keep it expensive.

Free-trade advocates also complain, saying that a private business has used the shelter of the federal sugar program, created in the Depression to nurture struggling farmers, to increase its corporate hammerlock.

“These people have been absolutely extorting consumers for decades, and the only reason they’re existing in the first place is, they were able to get sweet deals from governments that were propping them up,” says Sallie James, a trade policy analyst with the libertarian Cato Institute, referring to Florida Crystals and U.S. Sugar.

For the full story, see:

MARY WILLIAMS WALSH. “Florida Deal for Everglades May Help Big Sugar.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., September 14, 2008): 1 & 9.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

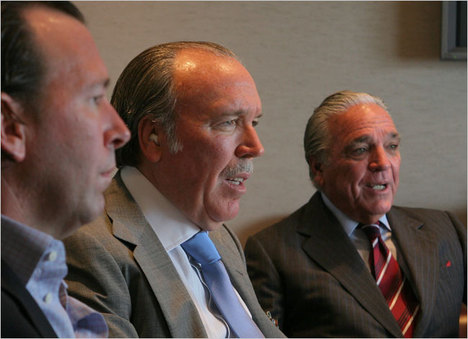

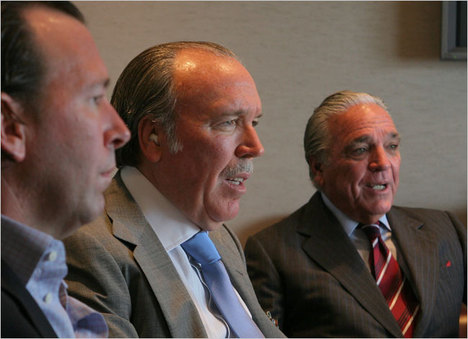

“Three leaders of the Fanjul family: Pepe Jr., left; J. Pepe, center; and Alfonso Jr., called Alfy. After Fidel Castro chased the family from Cuba, it rebuilt its sugar empire in the United States.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Three leaders of the Fanjul family: Pepe Jr., left; J. Pepe, center; and Alfonso Jr., called Alfy. After Fidel Castro chased the family from Cuba, it rebuilt its sugar empire in the United States.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

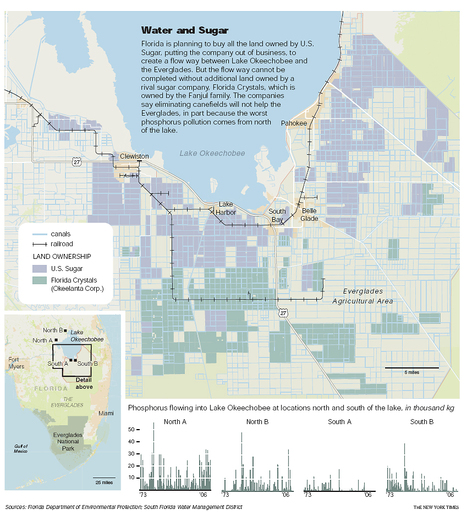

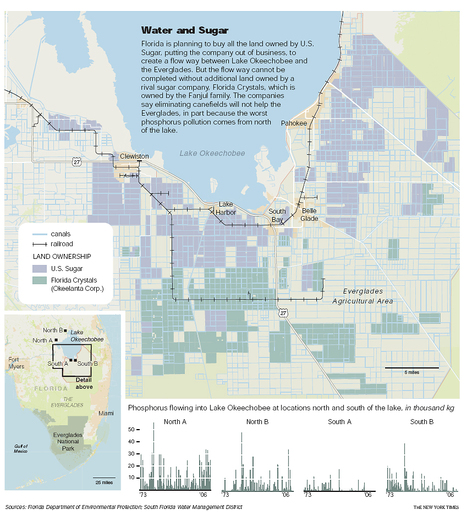

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.