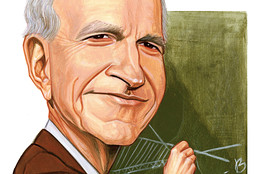

My friend Aloysius Siow and I were graduate students at the University of Chicago in the mid to late 1970s, where we took courses from Gary Becker, and attended his workshop. In the past, I have posted several entries on Becker on this blog that appear under the Category “Becker, Gary.” I expect to write some thoughts on his passing, but am not ready to do so yet. Aloysius drafted an obituary without delay, and kindly said it was OK for me to post it as an entry on this blog.

Obituary: Gary Becker

The Father of Economics ImperialismBy Aloysius Siow, Professor of Economics

University of Toronto

May 4, 2014Gary Becker, an American economist, died on May 3 at the age of 83.

His major contribution was the systematic application of economics to the analysis of social issues. Before his work, economists primarily studied how markets and market economies worked. He used economics to study discrimination, criminal behavior, human capital, marriage, fertility and other social issues.

He won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1992. He also won the John Bates Clark medal, awarded to the best American economist under 40, in 1967; and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor award by the US president to a civilian, in 2007.

Becker’s father, Louis William Becker, migrated from Montreal to the United States at age sixteen and moved several times before settling down in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Becker’s mother was Anna Siskind. He was born in Pottsville in 1930. At age five, Gary and his family moved to Brooklyn. He studied in Princeton University as an undergraduate. He did his PhD at the University of Chicago where he met Milton Friedman who would have an enormous influence on his intellectual development. After he obtained his PhD, Becker spent a few years as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago and then moved to Columbia University.

His path breaking 1955 dissertation was on the economics of discrimination. It was the first systematic study of a non-traditional economic topic using economics. In it, he argued that the difference in wages between a majority and a minority group can be used to measure the extent of discrimination in the labor market. When one points out today that it is unfair that women earn 80 percent of what men make, they are channeling Becker. His thesis analyzed how the South African system of apartheid benefited Whites at the expense of Blacks in South Africa. This analysis predated the Anti-apartheid Boycott Movement of the West which started in 1959.

The methodology and concern of his thesis previewed his research career. At the time of the publication of his thesis in 1957, economics was a conservative discipline, restricting itself to the study of the behavior of markets and market economies. Becker set for himself the task of systematically applying the tools of economics to the study of social issues. At the beginning, his work was generally ignored if not actually denigrated within the profession. Economists were supposed to study more important concerns.

After studying discrimination, he provided a modern economic theory of criminal behavior. Together with his study on discrimination, this work inspired the development of the law and economics movement.

At Columbia University, he began a systematic study of human capital, the study of the allocation of time and other topics in labor economics. Together with his colleague Jacob Mincer, they wrote many of the important papers in labor economics and also produced many successful graduate students. For example, their graduate student, Michael Grossman, wrote his thesis on health economics where he applied economics to the study of individual maintenance of health. Today, health economics is a major field of study and a central pillar of health policy. Due to the topics they worked on, they also attracted and successfully supervised many female PhD students. Claudia Goldin of Harvard University is perhaps his most illustrious female PhD student.

In 1970, Becker returned to the University of Chicago where he remained as a professor until his death. He continue to apply his economics to the study of the family, including the behavior of marriage markets, allocation of resources within the family and fertility behavior. The discussion of how economics can affect fertility anticipated government policies which seek to increase their native fertility rates. For example, Singapore has over 30 programs which seeks to increase her fertility rate.

Today, Becker’s approach is known as the rational choice approach in the social sciences. As the economics profession grew to appreciate his contributions, other social sciences have mixed feelings about his influence. On the one hand, they appreciate how he led economists to study different social issues. On the other hand, other social scientists often feel threatened by the invasion of economists.

Economists systematically use mathematical methods, statistical analysis and often large data sets. They prioritize cost benefit calculus over other factors which may also affect individual behavior. They had little patience with qualitative studies. Thus some social scientists felt that their contributions were unfairly ignored and so resisted the application of economics to their fields. For example, the Critical Legal Studies movement was developed in the 1970s in part in reaction to the success of the law and economics movement in law schools. In political science, rational choice theory is now a core field of study. Yet there are many political scientists who reject this approach.

Interestingly, motivated by the work of psychologists, economists have also begun to reject the purely rational calculus model of Becker as too narrow. Rather, these behavioral economics researchers argue that individuals have bounded rationality and are subject to systematic biases in their behavior. For example, Robert Shiller, a Nobel economist, has argued that bubbles occur in asset markets due to psychological biases. Thus the success of Becker has led to qualifications which is a hallmark of progress in science.

Contrary to many successful economists, Becker did not spend much time consulting for either the government or business. He was a conservative but unlike his mentor Milton Friedman, his direct influence on policy was minimal. Rather, the various economic fields which he instigated have had and continue to have significant influence on public policy. For example, every politician who wants to spend more resources on public education says that they are investing in the human capital of their society. Today, economists systematically contribute to policy discussions on maternity leaves, subsidies for child care and other social issues.

On a personal note, I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in the late seventies where I met Gary Becker. I was interested in social issues. But because he was so intimidating as a scholar, I did not write my thesis under him nor was it on those concerns. Ten years after I obtained my PhD, and after I had moved to the University of Toronto, I wrote my first paper on the economics of the family motivated by a discussion in evolutionary psychology. Our interest on the economics of the family overlapped and we subsequently have had many professional interactions. I also began to realize that he did not know everything and that it is fine to work on topics which he had worked on.

Later in his life, he would sometimes introduce me as a former PhD student. At first I would correct him. But later I did not because perhaps he was right.