(p. A13) The newly arrived Nukak do not provide much detail about why they left. They just say that "the Green Nukak," a possible reference to Marxist guerrillas, who wear camouflage, told them to leave.

"The Green Nukak said we could not keep walking in the jungle, or else there would be problems," explained Va-di, another Nukak man, whose words were translated from Nukak by Belisario. "The Green Nukak told us to go where it is safe."

. . .

In Aguabonita, the scene on a recent day was full of commotion and laughter. Naked children tugged at the shirts of two foreign journalists, offering big smiles and hugs. The men quickly welcomed the visitors into a makeshift shelter, where they laughed at some of the questions and, it seemed, wholly innocently at their own odd predicament.

Are they sad? "No!" cried a Nukak named Pia-pe, to howls of laughter. In fact, the Nukak said they could not be happier. Used to long marches in search of food, they are amazed that strangers would bring them sustenance — free.

What do they like most? "Pots, pants, shoes, caps," said Mau-ro, a young man who went to a shelter to speak to two visitors.

Ma-be added, "Rice, sugar, oil, flour." Others said they loved skillets. Also high on the list were eggs and onions, matches and soap and certain other of life’s necessities.

"I like the women very much," Pia-pe said, to raucous laughs.

One young Nukak mother, Bachanede, breast-feeding her infant as she talked, said she was happy just to stay still. "When you walk in the jungle," she said, "your feet hurt a lot."

The men still go into the jungle, searching for monkeys, a delicacy the Nukak cannot seem to live without. Monkeys are grilled, dismembered and boiled, then eaten piece by piece. The women still spend their time carefully weaving intricate wristbands and hammocks, using threads from palm leaves.

All live in shelters now, enjoy constant medical attention and, on weekends, stroll into town to take in the sights. "Nukak life is hard in the jungle," Dr. Maldonado said. "You wake up thinking about food and you go hunt, you go search for nuts. So when they see us they think their food problems are over."

That is not to say the Nukak do not have plans.

Ma-be explained that the idea is to grow plantains and yucca and take the crops to town. "We can exchange it for money," he said, "and exchange the money for other things." But first they need to learn how to cultivate crops. The Nukak say they would like their children to go to school. They also say they do not want to lose traditions, like hunting or speaking their language. "We do want to join the white family," Pia-pe said, speaking of Colombian society, "but we do not want to forget words of the Nukak."

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0060957573/ref=ed_oe_p/104-5180402-9681554?%5Fencoding=UTF8

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0060957573/ref=ed_oe_p/104-5180402-9681554?%5Fencoding=UTF8

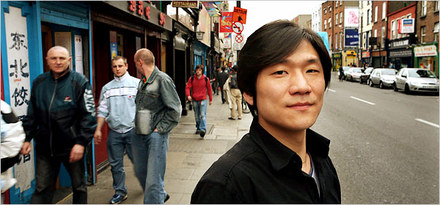

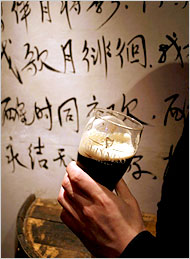

"his customers, in an unspoken gesture of good will, drink each other’s national beers." Source of caption, and photo:

"his customers, in an unspoken gesture of good will, drink each other’s national beers." Source of caption, and photo: