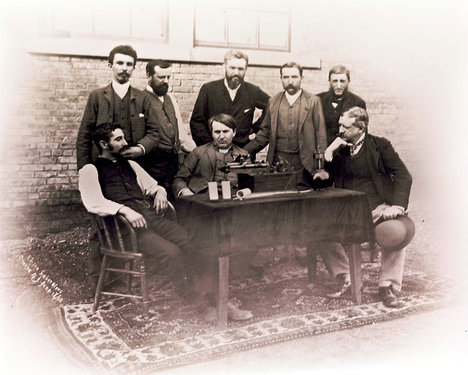

“EUROPEAN JOURNEY; Thomas Edison, seated center, sent Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann, standing behind him, to France in 1889. From there Wangemann traveled to Germany to record recitations and performances.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“EUROPEAN JOURNEY; Thomas Edison, seated center, sent Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann, standing behind him, to France in 1889. From there Wangemann traveled to Germany to record recitations and performances.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Edison is often ridiculed for failing to foresee that playing music would be a major use for his phonograph invention. (Nye 1991, p. 142 approvingly references Hughes 1986, p. 201 on this point.) But if Edison failed to foresee, then why did he assign Wangemann to make the phonograph “a marketable device for listening to music”?

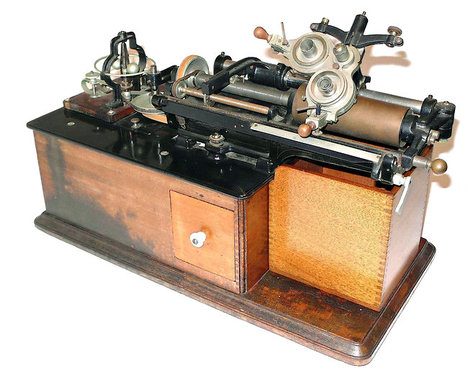

(p. D3) Tucked away for decades in a cabinet in Thomas Edison’s laboratory, just behind the cot in which the great inventor napped, a trove of wax cylinder phonograph records has been brought back to life after more than a century of silence.

The cylinders, from 1889 and 1890, include the only known recording of the voice of the powerful chancellor Otto von Bismarck. . . . Other records found in the collection hold musical treasures — lieder and rhapsodies performed by German and Hungarian singers and pianists at the apex of the Romantic era, including what is thought to be the first recording of a work by Chopin.

. . .

The lid of the box held an important clue. It had been scratched with the words “Wangemann. Edison.”

The first name refers to Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann, who joined the laboratory in 1888, assigned to transform Edison’s newly perfected wax cylinder phonograph into a marketable device for listening to music. Wangemann became expert in such strategies as positioning musicians around the recording horn in a way to maximize sound quality.

In June 1889, Edison sent Wangemann to Europe, initially to ensure that the phonograph at the Paris World’s Fair remained in working order. After Paris, Wangemann toured his native Germany, recording musical artists and often visiting the homes of prominent members of society who were fascinated with the talking machine.

Until now, the only available recording from Wangemann’s European trip has been a well-known and well-worn cylinder of Brahms playing an excerpt from his first Hungarian Dance. That recording is so damaged “that many listeners can scarcely discern the sound of a piano, which has in turn tarnished the reputations of both Wangemann and the Edison phonograph of the late 1880s,” Dr. Feaster said. “These newly unearthed examples vindicate both.”

For the full story, see:

RON COWEN. “Restored Edison Records Revive Giants of 19th-Century Germany.” The New York Times (Tues., January 31, 2012): D3.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated January 30, 2012.)

“Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann used a phonograph to record the voice of Otto von Bismarck.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Adelbert Theodor Edward Wangemann used a phonograph to record the voice of Otto von Bismarck.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.