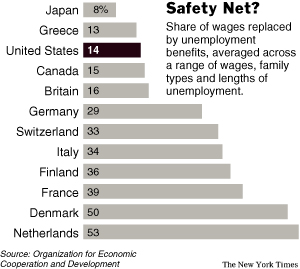

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

For awhile, during the Clinton administration, many Democratic economists, such as Alan Blinder, seemed to solidly support free trade as an engine for economic growth. But now several Democratic economists, such as Blinder as described in the excerpt below, seem to be returning to the usual Democratic protectionist policies.

If the goal is economic progress and growth, such policies remain ill-advised, no matter how effective they are at helping Democrats to win elections. To whit: Ed Leamer provides the arguments and evidence against worries about outsourcing in his long, but excellent, review of Thomas Friedman’s hand-wringing in The World is Flat. (See way below for the reference.)

(p. A14) Mr. Blinder’s job-loss estimates in particular are electrifying Democratic candidates searching for ways to address angst about trade. "Alan, because of his stature, provided a degree of legitimacy to what many of us had come to feel anecdotally — that the anxiety over outsourcing and offshoring was a far larger phenomenon than traditional economic analysis was showing," says Gene Sperling, an adviser to President Clinton and, now, to Hillary Clinton. Her rival, Barack Obama, spent an hour with Mr. Blinder earlier in this year.

Mr. Blinder’s answer is not protectionism, a word he utters with the contempt that Cold Warriors reserved for communism. Rather, Mr. Blinder still believes the principle British economist David Ricardo introduced 200 years ago: Nations prosper by focusing on things they do best — their "comparative advantage" — and trading with other nations with different strengths. He accepts the economic logic that U.S. trade with large low-wage countries like India and China will make all of them richer — eventually. He acknowledges that trade can create jobs in the U.S. and bolster productivity growth.

But he says the harm done when some lose jobs and others get them will be far more painful and disruptive than trade advocates acknowledge. He wants government to do far more for displaced workers than the few months of retraining it offers today. He thinks the U.S. education system must be revamped so it prepares workers for jobs that can’t easily go overseas, and is contemplating changes to the tax code that would reward companies that produce jobs that stay in the U.S.

His critique puts Mr. Blinder in a minority among economists, most of whom emphasize the enormous gains from trade. "He’s dead wrong," says Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati, who will debate Mr. Blinder at Harvard in May over his assertions about the magnitude of job losses from trade. Mr. Bhagwati says that in highly skilled fields such as medicine, law and accounting, "If we do a real balance sheet, I have no doubt we’re creating far more jobs than we’re losing."

. . .

He was silent when his former Princeton student, N. Gregory Mankiw, then chairman of President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, unleashed a political firestorm by reciting standard theory but appearing indifferent to pain caused to those whose jobs go overseas. "Does it matter from an economic standpoint whether items produced abroad come on planes and ships or over fiber optic cables?" Mr. Mankiw said at a February 2004 briefing. "Well, no, the economics is basically the same….More things are tradable than…in the past, and that’s a good thing."

Mr. Blinder says he agreed with Mr. Mankiw’s point that the economics of trade are the same however imports are delivered. But he’d begun to wonder if the technology that allowed English-speaking workers in India to do the jobs of American workers at lower wages was "a good thing" for many Americans. At a Princeton dinner, a Wall Street executive told Mr. Blinder how pleased her company was with the securities analysts it had hired in India. From New York Times’ columnist Thomas Friedman’s 2005 book, "The World is Flat," he found anecdotes about competition to U.S. workers "in walks of life I didn’t know about."

Mr. Blinder began to muse about this in public. At a Council on Foreign Relations forum in January 2005 he called "offshoring," or the exporting of U.S. jobs, "the big issue for the next generation of Americans." Eight months later on Capitol Hill, he warned that "tens of millions of additional American workers will start to experience an element of job insecurity that has heretofore been reserved for manufacturing workers."

At the urging of former Clinton Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, Mr. Blinder wrote an essay, "Offshoring: The Next Industrial Revolution?" published last year in Foreign Affairs. "The old assumption that if you cannot put it in a box, you cannot trade it is hopelessly obsolete," he wrote. "The cheap and easy flow of information around the globe…will require vast and unsettling adjustments in the way Americans and residents of other developed countries work, live and educate their children." (Read that full article.)

. . .

Diana Farrell, head of the McKinsey Global Institute, a pro-globalization think-tank arm of the consulting firm that has done its own analysis of vulnerable jobs, calls Mr. Blinder "an alarmist" and frets about the impact he is having on politicians, particularly the Democrats who see resistance to free trade as a political winner. She insists many jobs that could go overseas won’t actually go.

Ms. Farrell says Mr. Blinder’s work doesn’t take into account the realities of business which make exporting of some jobs impractical or which create offsetting gains elsewhere in the U.S. economy. He counters he is looking further into the future than McKinsey — 10 or 20 years instead of five — and expects more technological change than the consultants do "even without the Buck Rogers stuff."

For the full story, see:

DAVID WESSEL and BOB DAVIS. "JOB PROSPECTS; Pain From Free Trade Spurs Second Thoughts; Mr. Blinder’s Shift Spotlights Warnings Of Deeper Downside." The Wall Street Journal (Weds., March 28, 2007): A1 & A14.

(Note: ellipses added.)

For Leamer’s wonderful riff on why we need not worry about outsourcing, see:

Leamer, Edward E. "A Flat World, a Level Playing Field, a Small World after All, or None of the Above? A Review of Thomas L. Friedman’s the World Is Flat." Journal of Economic Literature 45, no. 1 (March 2007): 83-126.

Alan S. Blinder. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Alan S. Blinder. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

The guide told us that this area of pillars at Chichen Itza, in the Yucatan of Mexico, is thought to have been a market area. (Photo taken by me on April 8, 2007, at the excursion to Chichen Itza arranged for the Association of Private Enterprise Education.)

The guide told us that this area of pillars at Chichen Itza, in the Yucatan of Mexico, is thought to have been a market area. (Photo taken by me on April 8, 2007, at the excursion to Chichen Itza arranged for the Association of Private Enterprise Education.)

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Alan S. Blinder. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Alan S. Blinder. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Yellowcake, which is processed uranium, is in the third jar from the left of the top photo. The photo below it is of old equipment at a dormant uranium mine. Source of the photos and the graphic: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

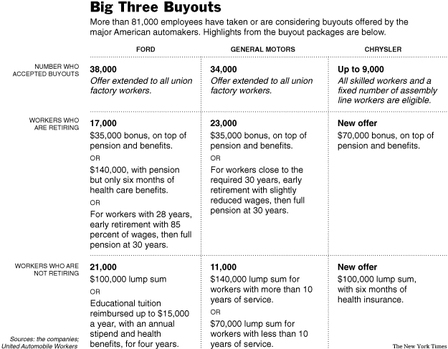

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.