“As a World Heritage site, Djenné, Mali, must preserve its mud-brick buildings, from the Great Mosque, in the background, to individual homes.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“As a World Heritage site, Djenné, Mali, must preserve its mud-brick buildings, from the Great Mosque, in the background, to individual homes.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 4) DJENNÉ , Mali — Abba Maiga stood in his dirt courtyard, smoking and seething over the fact that his 150-year-old mud-brick house is so culturally precious he is not allowed to update it — no tile floors, no screen doors, no shower.

“Who wants to live in a house with a mud floor?” groused Mr. Maiga, a retired riverboat captain.

With its cone-shaped crenellations and palm wood drainage spouts, the grand facade seems outside time and helps illustrate why this ancient city in eastern Mali is an official World Heritage site.

But the guidelines established by Unesco, the cultural arm of the United Nations, which compiles the heritage list, demand that any reconstruction not substantially alter the original.

“When a town is put on the heritage list, it means nothing should change,” Mr. Maiga said. “But we want development, more space, new appliances — things that are much more modern. We are angry about all that.”

. . .

Mahamame Bamoye Traoré, the leader of the powerful mason’s guild, surveyed the cramped rooms of the retired river boat captain’s house, naming all the things he would change if the World Heritage rules were more flexible.

“If you want to help someone, you have to help him in a way that he wants; to force him to live in a certain way is not right,” he said, before lying on the mud floor of a windowless room that measured about 6 feet by 3 feet.

“This is not a room,” he said. “It might as well be a grave.”

For the full story, see:

NEIL MacFARQUHAR. “Ancient City in Mali Rankled by Rules for Life in Cultural Spotlight.” The New York Times, First Section (Sun., January 9, 2011): 4.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated January 8, 2011 and had the title “Mali City Rankled by Rules for Life in Spotlight.”)

“Many residents of Djenné say they long for more modern homes, but Unesco preservation guidelines limit alterations to original structures.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Many residents of Djenné say they long for more modern homes, but Unesco preservation guidelines limit alterations to original structures.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

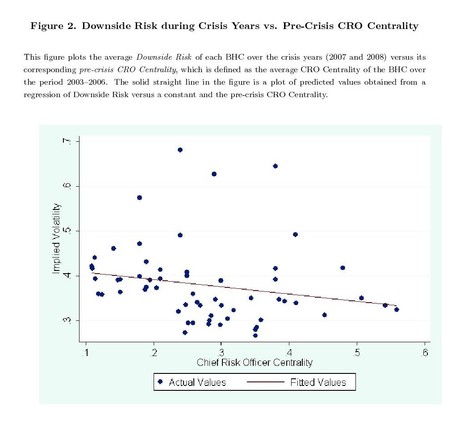

Source of graph: screen capture from p. 43 of NBER paper referenced below.

Source of graph: screen capture from p. 43 of NBER paper referenced below.