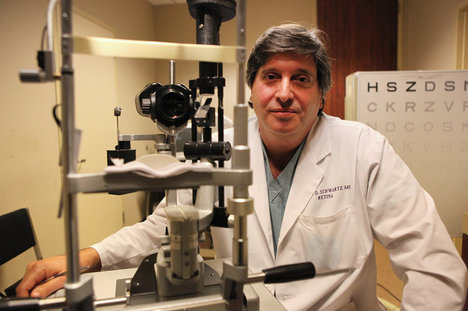

“The creators of the TikTok Watchband, left, and the Elevation Dock have raised far more money on Kickstarter than they initially sought.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“The creators of the TikTok Watchband, left, and the Elevation Dock have raised far more money on Kickstarter than they initially sought.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. B1) Kickstarter is a “crowd-funding” site. It’s a place for creative people to get enough start-up money to get their projects off the ground. The categories include music, film, art, design, food, publishing and technology. The projects seeking support might be recording a CD, putting on a play, producing a short film or developing a cool new tech product.

Suppose you’re the one who needs money. You describe your project with a video, a description and a target dollar amount. Listing your project is free.

If the citizens of the Web pledge enough money to meet your target by the deadline you set, then you get your money and (p. B7) you proceed with your project. At that point, Kickstarter takes 5 percent, and you pay 3 to 5 percent to Amazon.com’s credit card service.

If you don’t raise the money by the deadline, the deal is off. Your contributors keep their money, and Kickstarter takes nothing.

But here’s the part I had trouble understanding: These are not investments. If you make a pledge, you’ll never see your money again, even if the play, movie or gadget becomes a huge hit. You do get some little memento of your financial involvement — a T-shirt or a CD, for example, or a chance to preorder the gadget being developed — but nothing else tangible. Not even a tax deduction.

Furthermore, you have no guarantee that the project will even see the light of day. All kinds of things happen between inspiration and production. People lose interest, get married, move away, have trouble lining up a factory. The whole thing dies, and it was all for nothing.

So why, I kept wondering, does anybody participate? Who would give money for so little in return?

. . .

I started reading about . . . projects. The one that seemed to be drumming up the most interest lately is called the Elevation Dock. It’s just a charging stand for the iPhone, but wow, what a stand. It’s exquisitely milled from solid, Applesque aluminum. You don’t have to take your iPhone (or iPod Touch) out of its case to insert it into this dock. And the dock is solid enough that you can yank the phone out of it with one hand. The dock stays on the desk.

. . .

Other projects seeking your support: Jaja, a drawing stylus for iPad and Android tablets that’s pressure-sensitive (makes fatter lines when you bear down harder); LED Side Glow Hats (baseball caps with illuminated brims for working in dark places); Eye3 (an inexpensive flying drone for aerial photography); and so on.

Not all of them will reach their financing goals (only 44 percent do). Even fewer will wind up on store shelves.

But in dark economic times, Kickstarter offers aspirational voyeurism: you can read about the big dreams of the little people. And you can give the worthy artists a small financial vote of confidence — and enjoy the ride with them.

For the full story, see:

DAVID POGUE. “STATE OF THE ART; Embracing the Mothers of Invention.” The New York Times (Thurs., January 26, 2012): B1 & B7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article was dated January 25, 2012.)