Source of book image: http://perseuspromos.com/images/covers/200/9780465019267.jpg

(p. 777) Climatopolis begins with the assumption that our future will bring some combination of higher temperatures, sea level rise, more intense natural disasters, and changes in precipitation and drought conditions. The forecast is considered inevitable because of humanity’s deep and (p. 778) growing dependence on energy from fossil fuels, the burning of which generates emissions that cause climate change. In a way that some readers are likely to find overly pessimistic, dismissive, or both, Kahn asserts that we are unlikely to invent a “magical” technology that allows us to live well without producing greenhouse gases. He is equally skeptical about whether geo-engineering will help stabilize the climate. So when it comes to facing a future that includes climate change, Kahn has concluded as soon as page 5 that “unlike a ship, we cannot turn away.”

Economics is, after all, the dismal science, but early pessimism in Climatopolis quickly gives way to an overall optimistic theme. It is first encountered, somewhat surprisingly, in a chapter titled “What We’ve Done When Our Cities Have Blown Up.” With examples that range from fires and floods to wars and terrorist attacks, Kahn makes the case that we humans are a surprisingly resilient species. Among the lessons he draws are that destruction often triggers economic booms, people learn from their mistakes, cities are shaped by the accumulation of small decisions by millions of self-interested people, and when conditions are bad in one location people migrate to where it is better.

Kahn gets traction out of the notion that people “vote with their feet,” and he describes how climate change will affect where people want to go. Rising temperatures will cause Sun Belt cities in the United States to suffer, for example, while northern cities such as Minneapolis and Detroit will become more attractive places to live.

. . .

Climatopolis . . . cautions against maladaptive policies, and the recommendation here will be familiar to economists: prices should be left undistorted to reflect real costs and risks. Kahn is critical of a policy in Los Angeles under which people who demand more water pay a lower marginal price, and thereby face exactly the wrong incentive for conservation as water becomes increasingly scarce. He also points to the problems of subsidized insurance or caps on premiums for residents in climate-vulnerable areas, as these policies only promote greater vulnerability. What is more, Kahn would like us to stop treating people who move into harm’s way as victims in need of a bailout when natural disasters strike. He writes that, “Ironically, to allow capitalism to help us adapt to climate change, the government must precommit to not protect ‘the victims’.”

For the full review, see:

Kotchen, Matthew J. “Review of Kahn’s Climatopolis.” Journal of Economic Literature 49, no. 3 (September 2011): 777-79.

(Note: ellipses added.)

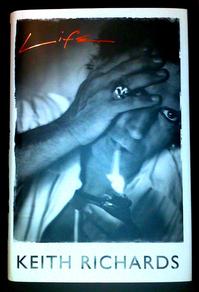

Book under review:

Kahn, Matthew E. Climatopolis: How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future. New York: Basic Books, 2010.