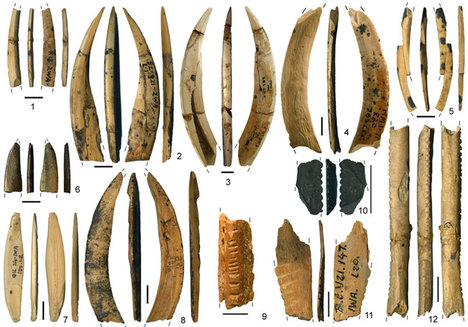

“ARTIFACTS; The excavations have uncovered caches of advanced stone hunting tools, including spear tips and other small blades, or microliths, which suggest that modern Homo sapiens in Africa had a grasp of complex technologies. The research team’s report challenges a Eurocentric theory of modern human development.” [This photo shows spear tips; another photo included with the article showed three small blades (aka microliths).] Source of quoted part of caption and of photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. D3) At a rock shelter on a coastal cliff in South Africa, scientists have found an abundance of advanced stone hunting tools with a tale to tell of the evolving mind of early modern humans at least 71,000 years ago.

. . .

“Ninety percent of scientists are comfortable that fully modern humans and human cognition developed in Africa,” Dr. Marean said. “Now they have moved on. The questions are, how much earlier than 71,000 years did these behaviors emerge? Was it an accretionary process, or was it an abrupt event? Did these people have language by this time?”

Like many other archaeologists, Dr. Marean and his team have concentrated their investigations in the caves and rock shelters overlooking the Indian Ocean. In a global ice age beginning 72,000 years ago, many Africans fled the continent’s arid interior, heading for the more benign southern shore. Access to seafood and more plentiful plant and animal resources may have increased populations and encouraged technological advances, Dr. Marean said.

The well-preserved artifacts at Pinnacle Point, collected over a recent 18-month period, led the researchers to conclude that the advanced technologies in Africa “were early and enduring.” Other archaeologists who reached different conclusions may have been misled by the “small sample of excavated sites,” they said.

Richard G. Klein, a paleoanthropologist at Stanford University who has favored a more sudden and recent origin of modern behavior, about 50,000 years ago, questioned the reliability of the dating method for the tools, noting that “there is another team that has already argued for a much longer” time period for the toolmaking culture.

. . .

The hypothesis of earlier African origins of modern human behavior and cognition has been gaining strength over the last decade or two. Two archaeologists, Alison S. Brooks of George Washington University and Sally McBrearty of the University of Connecticut, led the charge with publications of their analysis of increasing evidence of African art and ornamentations expressing a modern cognitive capacity and symbolic thinking.

In a commentary accompanying the Nature report, Dr. McBrearty, who was not involved in the research, wrote that she believed that “modern cognitive capacity emerged at the same time as modern anatomy, and that various aspects of human culture arose gradually” over the course of subsequent millenniums.

For the full story, see:

JOHN NOBLE WILFORD. “Stone Tools Point to Creative Work by Early Humans in Africa.” The New York Times (Tues., November 13, 2012): D3.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date November 12, 2012.)

The research discussed in the passages quoted above, appeared in Nature:

Brown, Kyle S., Curtis W. Marean, Zenobia Jacobs, Benjamin J. Schoville, Simen Oestmo, Erich C. Fisher, Jocelyn Bernatchez, Panagiotis Karkanas, and Thalassa Matthews. “An Early and Enduring Advanced Technology Originating 71,000 Years Ago in South Africa.” Nature 491, no. 7425 (22 November 2012): 590-93.