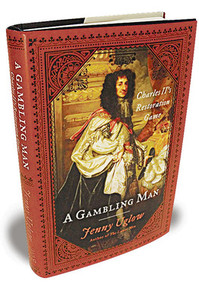

Source of book image: online version of the WSJ review quoted and cited below.

(p. A19) Early in “A Gambling Man,” a detailed and thoroughly engrossing examination of the Restoration’s first decade, Jenny Uglow notes that Charles Stuart, upon his ascension, “wanted passionately to be seen as the healer of his people’s woes and the glory of his nation.” Cromwell’s regime had featured constant war and constant taxes. The population was bitterly divided among Anglicans, Catholics and dissenting Protestants–Presbyterians, Puritans, Quakers, Baptists. A huge standing army had burdened the people financially and frightened them; such an army, it was not unreasonably thought, could be used to impose a tyranny.

. . .

As a result of such divisions, Charles became a “gambler,” as Ms. Uglow puts it–not at cards or gaming tables but at affairs of state. His biggest gamble was on something he fervently wanted to achieve: religious toleration for all sects and the freedom for Englishmen to follow their own “tender consciences” in individual worship. He forwarded this policy in Parliament only to receive his first major defeat with the passage of the Corporation Act, a law that took the power of corporations (governing towns and businesses) away from Nonconformists and handed it back to the Church of England. Charles had gambled on “the force of reasonable argument,” Ms. Uglow says, but was ultimately defeated “by the entrenched interests of the [Anglican] Church” and “the deep-held suspicions” of Parliament, which believed that England’s dissenting sects posed a persistent threat. That Charles was willing to go head-to-head with Parliament for such a cause, even in failure, was especially audacious, considering his father’s fate.

. . .

In his desire to be a monarch of the people, Charles was determined to make himself accessible–in the early days of his reign he threw open the palace of Whitehall to all comers. He gambled, with some success, that (in Ms. Uglow’s words) “easy access would make people of all views feel they might reach him, preventing conspiracies.” During the 1666 Great Fire of London he and his brother, James, duke of York, went out into the streets and put themselves alongside soldiers and workmen. They could be seen “filthy, smoke-blackened and tired,” frantically creating a firebreak as the blaze consumed London like a monstrous beast.

For the full review, see:

NED CRABB. “BOOKSHELF; Risky Business; A bitterly divided nation, a monarchy splendiferously restored..” The Wall Street Journal (Fri., NOVEMBER 27, 2009): A19.

(Note: ellipses added; bracketed word in original.)

(Note: the online version of the review is dated NOVEMBER 26, 2009.)

Book being reviewed:

Uglow, Jenny. A Gambling Man: Charles II’s Restoration Game. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.