The clip above is embedded from You Tube. It was recorded on July 6, 2011 in Mammel Hall, the location of the College of Business at the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO). I am grateful to Charley Reed of UNO University Relations for doing a great job of shooting and editing the clip.

Category: Creative Destruction

In 1880s Prices Fell Because of Technological Progress

Michael Perelman has strongly suggested that I read David Well’s book. It is on my “to do” list.

(p. C10) The dull title of “Recent Economic Changes” does no justice to David A. Wells’s fascinating contemporary account of a deflationary miasma that settled over the world’s advanced economies in the 1880s. His cheery conclusion: Prices were falling because technology was progressing. What had pushed the price of a bushel of wheat down to 67 cents in 1887 from $1.10 in 1882 was nothing more sinister than the opening up of new regions to cultivation (Australia, the Dakotas) and astounding improvements in agricultural machinery.

For the full review, see:

JAMES GRANT. “FIVE BEST; Little-Known Gold From the Gilded Age.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., AUGUST 6, 2011): C10.

Source of book under review:

Wells, David A. Recent Economic Changes and Their Effect on Production and Distribution of Wealth and Well-Being of Society. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1889.

Michael Perelman argues that in Recent Economic Changes, David Wells anticipates the substance, although not the wording, of Schumpeter’s “creative destruction”:

Perelman, Michael. “Schumpeter, David Wells, and Creative Destruction.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 9, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 189-97.

Capitalism Was Not Inevitable

Source of book image:

http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/519PfT2oUtL.jpg

(p. 15) What is the nature of capitalism? For Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian-born economist whose writings have acquired a special relevance in the past year or two, this most modern of economic systems “incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” Capitalism, Schumpeter proclaimed, cannot stand still; it is a system driven by waves of entrepreneurial innovation, or what he memorably described as a “perennial gale of creative destruction.”

Schumpeter died in 1950, but his ghost looms large over Joyce Appleby’s splendid new account of the “relentless revolution” unleashed by capitalism from the 16th century onward. Appleby, a distinguished historian who has dedicated her career to studying the origins of capitalism in the Anglo-American world, here broadens her scope to take in the global history of capitalism in all its creative — and destructive — glory.

She begins “The Relentless Revolution” by noting that the rise of the economic system we call capitalism was in many ways improbable. It was, she rightly observes, “a startling departure from the norms that had prevailed for 4,000 years,” signaling the arrival of a new mentality, one that permitted private investors to pursue profits at the expense of older values and customs.

In viewing capitalism as an extension of a culture unique to a particular time and place, Appleby is understandably contemptuous of those who posit, in the spirit of Adam Smith, that capitalism was a natural outgrowth of human nature. She is equally scornful of those who believe that its emergence was in any way inevitable or inexorable.

. . .

. . . , she captures how a new generation of now forgotten economic writers active long before Adam Smith built a case “that the elements in any economy were negotiable and fluid, the exact opposite of the stasis so long desired.” This was a revolution of the mind, not machines, and it ushered in profound changes in how people viewed everything from usury to joint stock companies. As she bluntly concludes, “there can be no capitalism . . . without a culture of capitalism.”

. . .

The individual entrepreneur is at the center of her analysis, and her book offers thumbnail sketches of British innovators from James Watt to Josiah Wedgwood. She continues on to the United States and Germany, giving readers a whirlwind tour of the lives and achievements of a host of men whom she calls “industrial leviathans” — Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Carnegie in the United States; Thyssen, Siemens and Zeiss in Germany. All created new industries while destroying old ones.

For the full review, see:

STEPHEN MIHM. “Capitalist Chameleon.” The New York Times Book Review (Sun., January 24, 2010): 15.

(Note: ellipses added except for the one in the “there can be no capitalism . . . without a culture of capitalism” quote.)

(Note: the online version of the review is dated January 22, 2010.)

Book under review:

Appleby, Joyce. The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Medieval Halls of the Rich Incubated Plague in a Nest of “Filth Unmentionable”

(p. 51) In even the best houses, floors were generally just bare earth strewn with rushes, harboring “spittle and vomit and urine of dogs and men, beer that hath been cast forth and remnants of fishes and other filth unmentionable,” as the Dutch theologian and traveler Desiderius Erasmus rather crisply summarized in 1524. New layers of rushes were laid down twice a year normally, but the old accretions were seldom removed, so that, Erasmus added glumly, “the substratum may be unmolested for twenty years.” The floors were in effect a very large nest, much appreciated by insects and furtive rodents, and a perfect incubator for plague. Yet a deep pile of flooring was generally a sign of prestige. It was common among the French to say of a rich man that he was “waist deep in straw.”

Source:

Bryson, Bill. At Home: A Short History of Private Life. New York: Doubleday, 2010.

Diamond to Teach Honors Colloquium on Creative Destruction in Fall 2011

Government Finally Allows Steve Jobs to Creatively Destroy His Own House

(p. A18) WOODSIDE, Calif. — There may not be an app for it, but Steve Jobs did have a permit. And with that, his epic battle to tear down his own house is finally over.

For the better part of the last decade, Mr. Jobs, the co-founder and chief executive of Apple, has been trying to demolish a sprawling, Spanish-style mansion he owns here in Woodside, a tony and techie enclave some 30 miles south of San Francisco, in hopes of building a new, smaller home on the lot. His efforts, however, had been delayed by legal challenges and cries for preservation of the so-called Jackling House, which was built in the 1920s for another successful industrialist: Daniel Jackling, whose money was in copper, not silicon.

. . .

“Steve Jobs knew about the historic significance of the house,” Mr. Turner said. “And unfortunately he disregarded it.”

Mr. Turner said the mansion, which had 35 rooms in nearly 15,000 square feet of interior space, was significant in part because it was built by George Washington Smith, an architect who is known for his work in California. But Mr. Jobs had been dismissive of Mr. Smith’s talents, calling the house “one of the biggest abominations” he had ever seen.

For the full story, see:

JESSE McKINLEY. “With Demolition, Apple Chief Makes Way for House 2.0.” The New York Times (Fri., February 16, 2011): A18.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated February 15, 2011.)

Entrepreneur Ken Olsen Was First Lionized and Then Chastised

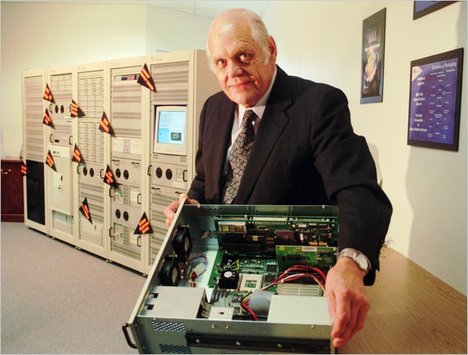

“Ken Olsen, the pioneering founder of DEC, in 1996.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Ken Olsen, the pioneering founder of DEC, in 1996.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

I believe in The Road Ahead, Bill Gates describes Ken Olsen as one of his boyhood heroes for having created a computer that could compete with the IBM mainframe. His hero failed to prosper when the next big thing came along, the PC. Gates was determined that he would avoid his hero’s fate, and so he threw his efforts toward the internet when the internet became the next big thing.

Christensen sometimes uses the fall of minicomputers, like Olsen’s Dec, to PCs as a prime example of disruptive innovation, e.g., in his lectures on disruptive innovation available online through Harvard. A nice intro lecture is viewable (but only using Internet Explorer) at: http://gsb.hbs.edu/fss/previews/christensen/start.html

(p. A22) Ken Olsen, who helped reshape the computer industry as a founder of the Digital Equipment Corporation, at one time the world’s second-largest computer company, died on Sunday. He was 84.

. . .

Mr. Olsen, who was proclaimed “America’s most successful entrepreneur” by Fortune magazine in 1986, built Digital on $70,000 in seed money, founding it with a partner in 1957 in the small Boston suburb of Maynard, Mass. With Mr. Olsen as its chief executive, it grew to employ more than 120,000 people at operations in more than 95 countries, surpassed in size only by I.B.M.

At its peak, in the late 1980s, Digital had $14 billion in sales and ranked among the most profitable companies in the nation.

But its fortunes soon declined after Digital began missing out on some critical market shifts, particularly toward the personal computer. Mr. Olsen was criticized as autocratic and resistant to new trends. “The personal computer will fall flat on its face in business,” he said at one point. And in July 1992, the company’s board forced him to resign.

For the full obituary, see:

GLENN RIFKIN. “Ken Olsen, Founder of the Digital Equipment Corporation, Dies at 84.” The New York Times (Tues., February 8, 2011): A22.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story is dated February 7, 2011 and has the title “Ken Olsen, Who Built DEC Into a Power, Dies at 84.”)

Gates writes in autobiographical mode in the first few chapters of:

Gates, Bill. The Road Ahead. New York: Viking Penguin, 1995.

Christensen’s mature account of disruptive innovation is best elaborated in:

Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

U.S. Holds “Edge in Its Openness to Innovation”

Source of book image: http://www.tower.com/tycoons-how-andrew-carnegie-john-d-rockefeller-jay-charles-r-morris-paperback/wapi/100346776?download=true&type=1

(p. 24) Judging by Charles R. Morris’s new book, “The Tycoons,” it takes about 100 years for maligned monopolists and “robber barons” to morph into admirable innovators.

Morris skillfully assembles a great deal of academic and anecdotal research to demonstrate that Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould and J. P. Morgan did not amass their fortunes by trampling on the downtrodden or ripping off consumers – . . .

. . .

Though Morris only hints at it, the truth is that the real heroes of the American industrial revolution were not his four featured tycoons, but the American people themselves. I don’t mean this to sound like a corny burst of patriotism. In the 19th century, the United States was still young. Most families had either been booted out of Europe or fled it, and they didn’t care about tradition or the Old Guard. With little to lose, they were willing to bet on a roll of the dice, even if it was they who occasionally got rolled. Europe was encrusted with guilds, unions and unbendable rules. Britons took half a day to make a rifle stock, because 40 different tradesmen poked their noses into the huddle. American companies polished off new rifle stocks in 22 minutes.

The United States still holds an edge in its openness to innovation. In 1982, French farmers literally chased the French agriculture minister, Edith Cresson, off their fields with pitchforks because she suggested reform. By contrast, back in the late 1850’s, Abraham Lincoln was a hot after-dinner speaker. Was he discussing slavery? No. The title of his talk was “Discoveries and Inventions.” The real root of economic growth is not natural resources or weather or individual genius. It’s attitude, not latitude. The Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called innovations gales of “creative destruction.” Americans, not Europeans, had the gall to stare into those gales – with optimism.

For the full review, see:

TODD G. BUCHHOLZ . “‘The Tycoons’: Benefactors of Great Wealth.” The New York Times Book Review (Sun., October 2, 2005): 24.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the title “‘The Tycoons’: Benefactors of Great Wealth.”)

Book under review:

Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Times Books, 2005.

Caballero Worries about the Relevance of Mainstream Macro Modeling

In the past, I have found some of MIT economist Ricardo Caballero’s research useful because he takes Schumpeter’s process of creative destruction seriously.

In a recent paper, he joins a growing number of mainstream economists who worry that the recent and continuing economic crisis has implications for the methodology of economics:

In this paper I argue that the current core of macroeconomics–by which I mainly mean the so-called dynamic stochastic general equilibrium approach–has become so mesmerized with its own internal logic that it has begun to confuse the precision it has achieved about its own world with the precision that it has about the real one. This is dangerous for both methodological and policy reasons. On the methodology front, macroeconomic research has been in “fine-tuning” mode within the local-maximum of the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium world, when we should be in “broad-exploration” mode. We are too far from absolute truth to be so specialized and to make the kind of confident quantitative claims that often emerge from the core. On the policy front, this confused precision creates the illusion that a minor adjustment in the standard policy framework will prevent future crises, and by doing so it leaves us overly exposed to the new and unexpected.

The paper has been published as:

Caballero, Ricardo J. “Macroeconomics after the Crisis: Time to Deal with the Pretense-of-Knowledge Syndrome.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24, no. 4 (Fall 2010): 85-102.

Internet Enabled Creative Destruction

(p. R4) To understand the challenges that faced businesses the past 10 years, consider the household names that didn’t make it through the decade: Anheuser-Busch, Compaq, Gillette, Enron, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, WorldCom.

. . .

As the decade rolled on, the Internet came to be known for destroying businesses. It upended decades-old business models in fields such as media, advertising, travel and entertainment, as consumers and advertisers migrated to the digital world.

But that same shift created opportunity. No one epitomized that better than Google Inc. A mere 15 months old at the beginning of the decade, it morphed from a startup technology company into an advertising and media powerhouse and is now plotting a move into communications. There, it will clash with Apple Inc., which was reborn following the return of co-founder Steve Jobs in 1997. Apple’s iPod and iTunes reshaped the music industry; its iPhone revolutionized communications by opening itself to independent innovators.

“This is what [Austrian economist Joseph] Schumpeter had in mind with his term ‘creative destruction,'” says Paul David, an economic historian at Stanford University. Industrial collapse is a “messy, messy process,” Mr. David says. “It’s a great drama, and watching it play out in this decade has been very interesting.”

For the full story, see:

SCOTT THURM. “Creativity, Meet Destruction; The Decade Rewrote the Corporate Handbook, Thanks to the Web, Globalization and the Collapse of Two Bubbles.” The Wall Street Journal (Mon., DECEMBER 21, 2009): R4.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated DECEMBER 22, 2009.)