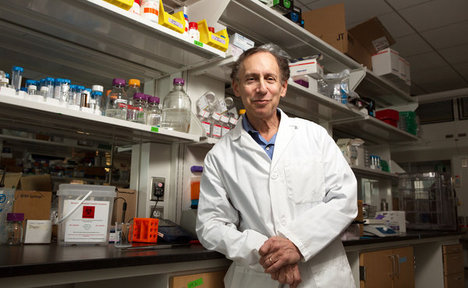

“Dr. Robert Langer’s research lab is at the forefront of moving academic discoveries into the marketplace.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

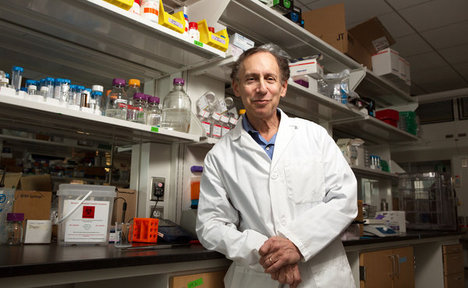

“Dr. Robert Langer’s research lab is at the forefront of moving academic discoveries into the marketplace.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 1) HOW do you take particles in a test tube, or components in a tiny chip, and turn them into a $100 million company?

Dr. Robert Langer, 64, knows how. Since the 1980s, his Langer Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has spun out companies whose products treat cancer, diabetes, heart disease and schizophrenia, among other diseases, and even thicken hair.

The Langer Lab is on the front lines of turning discoveries made in the lab into a range of drugs and drug delivery systems. Without this kind of technology transfer, the thinking goes, scientific discoveries might well sit on the shelf, stifling innovation.

A chemical engineer by training, Dr. Langer has helped start 25 companies and has 811 patents, issued or pending, to his name. More than 250 companies have licensed or sublicensed Langer Lab patents.

Polaris Venture Partners, a Boston venture capital firm, has invested $220 million in 18 Langer Lab-inspired businesses. Combined, these businesses have improved the health of many millions of people, says Terry McGuire, co-founder of Polaris.

. . .

(p. 7) Operating from the sixth floor of the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research on the M.I.T. campus in Cambridge, Mass., Dr. Langer’s lab has a research budget of more than $10 million for 2012, coming mostly from federal sources.

. . .

David H. Koch, executive vice president of Koch Industries, the conglomerate based in Wichita, Kan., wrote in an e-mail that “innovation and education have long fueled the world’s most powerful economies, so I can’t think of a better or more natural synergy than the one between academia and industry.” Mr. Koch endowed Dr. Langer’s professorship at M.I.T. and is a graduate of the university.

For the full story, see:

HANNAH SELIGSON. “Hatching Ideas, and Companies, by the Dozens at M.I.T.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., November 25, 2012): 1 & 7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date November 24, 2012.)