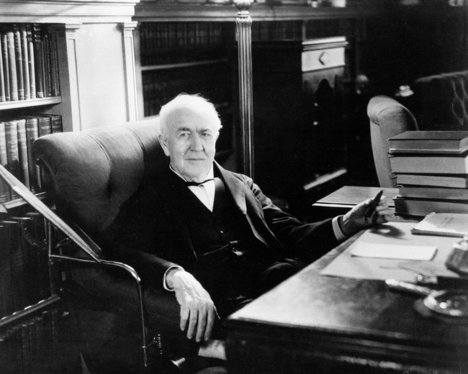

“Thomas Alva Edison.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Thomas Alva Edison.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

I have not read Stross’ books on Jobs and Edison. According to some of the Amazon reviews of the Jobs book, back in 1993 Stross was much more critical of Jobs than he is in the piece below:

(p. 4) I wrote a book about Mr. Jobs in 1993.

. . .

Years later, I wrote a biography of Edison, a person whom Mr. Jobs admired. When you compare the two personalities and their careers, a few similarities emerge immediately. Both had less formal schooling than most of their respective peers. Both possessed the ability to visualize projects on a grand scale. Both followed an inner voice when making decisions. And both had terrific tempers that could make their employees quake.

. . .

Mr. Jobs was the far shrewder businessman, even if he never talked about wealth as a matter of personal interest. When Edison died, he left behind an estate valued at about $12 million, or about $180 million in today’s dollars. His friend Henry Ford had once joked that Edison was “the world’s greatest inventor and the world’s worst businessman.” Mr. Jobs was worth a commanding $6.5 billion.

Mr. Jobs was perhaps the most beloved billionaire the world has ever known. Richard Branson’s tribute captures the way people felt they could identify with Mr. Jobs’s life narrative: “So many people drew courage from Steve and related to his life story: adoptees, college dropouts, struggling entrepreneurs, ousted business leaders figuring out how to make a difference in the world, and people fighting debilitating illness. We have all been there in some way and can see a bit of ourselves in his personal and professional successes and struggles.”

For the full commentary, see:

RANDALL STROSS. “The Power of Taking the Big Chance.” The New York Times, SundayBusiness Section (Sun., October 9, 2011): 4.

(Note: online version of the commentary is dated October 8, 2011, and has the title “The Wizard and the Mortal: Two Sides of Genius.”)

(Note: in the print version, the same title, on the same page, was used as heading for two different articles on Steve Jobs–Lohr’s on the left side, and Stross’ on the right side.)

Stross’ books on Jobs and Edison are:

Stross, Randall E. Steve Jobs & the Next Big Thing. New York: Scribner Publishers, 1993.

Stross, Randall E. The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World. New York: Crown Publishers, 2007.