Source of graphs: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

We all know that correlation is not the same as causation. The main cause of Egypt’s slow growth is its lack of institutions and policies supporting entrepreneurial capitalism, and not the decline of Egyptian cities. (But the decline of Egyptian cities does not help.)

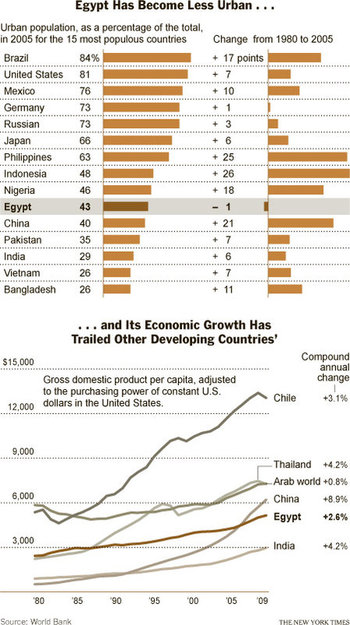

(p. B1) Since then, the cities of Asia have expanded rapidly, drawing in millions of peasant farmers looking for a better life — and, more often than not, finding it. Almost 50 percent of East Asians now live in cities. And Egypt? It is the only large country to have become less urban in the last 30 years, according to the World Bank. About 43 percent of Egyptians are city dwellers today.

This urban stagnation helps explain Egypt’s broader stagnation. As tough as city life in poor countries can be, it’s also fertile ground for economic growth. Nearly everything can be done more efficiently in a well-run city, be it plumbing, transportation or the generation of new ideas and businesses. “Being around other people,” says Paul Romer, the economist and growth expert, “helps make us smarter.”

Edward Glaeser, a Harvard economist (and weekly contributor to the Times’s Economix blog), has just published a book, “The Triumph of the City, making the case that cities are humanity’s greatest invention. Countries that become more urban tend to become far more productive, Mr. Glaeser writes. The effect is even bigger for poor countries than rich ones.

. . .

Three researchers — Michael Clemens, Lant Pritchett and Claudio Montenegro — recently found a novel way to measure how well various countries use the workers they have. The three compared the wages of immigrants to the United States with the wages of similar workers from the same country who remained home.

A 35-year-old urban Egyptian man with a high school education who moves to the United States can expect an incredible eightfold increase in living standards, the researchers found. Immigrants from only two countries, Yemen and Nigeria, receive a larger boost. In effect, these are the countries with the biggest gap between what their workers can produce in a different environment and what they are actually producing at home.

No wonder 19 percent of Egyptians told Gallup (well before the protests) that they would move to another country if they could. Mr. Clemens says that for every green card the United States awarded in a recent immigration lottery, 146 Egyptians had applied.

For the full commentary, see:

DAVID LEONHARDT. “Economic Scene; For Egypt, a Fresh Start, With Cities.” The New York Times (Weds., February 16, 2011): B1 & B11.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article was dated February 15, 2011.)

The scholarly article summarized is:

Clemens, Michael, Claudio Montenegro, and Lant Pritchett. “The Place Premium: Wage Differences for Identical Workers across the Us Border.” HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series # RWP09-004, January 2009.

The Glaeser book is:

Glaeser, Edward L. Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.