To explain the experience in the United States, one would have to believe that Americans have some better way of translating the new technology into productivity than other countries. And that is precisely what Professor Van Reenen’s research suggests.

His paper ”Americans Do I.T. Better: U.S. Multinationals and the Productivity Miracle,” (with Nick Bloom of Stanford University and Raffaella Sadun of the London School of Economics) looked at the experience of companies in Britain that were taken over by multinational companies with headquarters in other countries. They wanted to know if there was any evidence that the American genius with information technology transfers to locations outside the United States. If American companies turn computers into productivity better than anyone else, can businesses in Britain do the same when they are taken over by Americans?

And in the huge service sectors — financial services, retail trade, wholesale trade — they found compelling evidence of exactly that. American takeovers caused a tremendous productivity advantage over a non-American alternative.

When Americans take over a business in Britain, the business becomes significantly better at translating technology spending into productivity than a comparable business taken over by someone else. It is as if the invisible hand of the American marketplace were somehow passing along a secret handshake to these firms.

. . .

But there is a chance that the 1990s represent a fundamental shift in the global economy. Perhaps the greater amount of uncertainty and churn in the world economy in the 1990s is the new norm. Perhaps the 21st century will continually favor those who adjust best to changes. As Professor Van Reenen put it, ”If the world has become one in which everyone is trying to hit a moving target, it certainly helps to be the best at changing one’s aim.”

But that is, of course, the paradox of the American position. We hate experiencing major adjustments and industry transformations that force people to look for new jobs. That experience has made many skeptical about the future of the United States in the world economy. Yet the evidence seems to show that for all our dissatisfaction, we are the most flexible economy around and may be best poised to take advantage of the coming changes on a global scale precisely because we are so good at adjusting.

For the full commentary, see:

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: I thank Aaron Brown for calling the above article to my attention.)

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

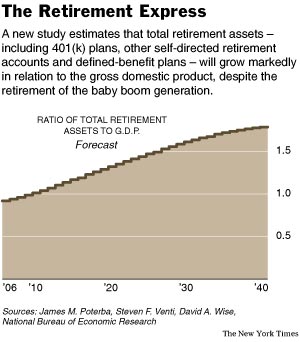

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article cited below. A CVS pharmacy MinuteClinic. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

A CVS pharmacy MinuteClinic. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited below.