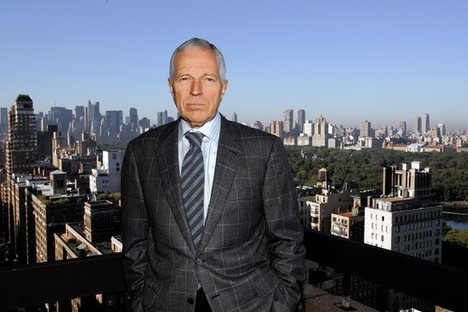

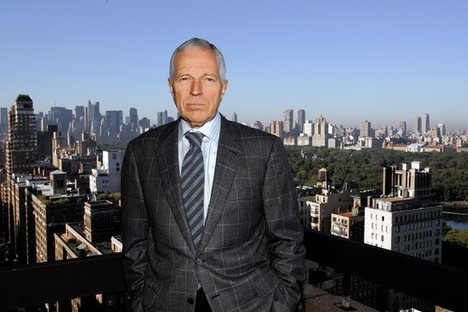

“Edmund Phelps, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize for economics.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ review quoted and cited below.

(p. C7) Edmund Phelps’s “Mass Flourishing” could easily be retitled “Contra-Corporatism,” for at its heart this fine book is an attack on that increasingly common “third way” between capitalism and socialism. Mr. Phelps cogently argues that America’s current economic woes reflect a reduction in the innovative dynamism that generates economic success and personal satisfaction. He places little hope in the Democratic Party, which “voices a new corporatism well beyond Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal or Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society,” or in Republicans in the thrall of “traditional values,” who see “the good economy as mercantile capitalism plus social protection and social insurance.” He instead yearns for legislative solons who “could usefully ask of every bill and regulatory directive: How would it impact the dynamism of our economy?”

. . .

The book eloquently discusses the culture of innovation, which can refer to both an entrepreneurial mind-set and the cultural achievements during an age of change. He sees modern capitalism as profoundly humanist, imbued with “a spirit that views the prospect of unanticipated consequences that may come with voyaging into the unknown as a valued part of experience and not a drawback.”

. . .

In . . . [the] new corporatism, the state protects both organized labor and politically connected companies. and the state has acquired a “panoply of new roles,” from regulations “aimed at shielding companies or workforces from competition” to lawsuits that “add to the diversion of income from earners to those receiving compensation or indemnification.” It is as if “every person in a society is a signatory to an implicit contract” in which “no person may be harmed by others without receiving compensation.” But protection against all conceivable harm also means protection against almost all change–and this is the death knell of dynamism and innovation.

. . .

But what is to be done? The author wants governments that are “aware of the importance of the role played by dynamism in a modern-capitalist economy,” and he disparages both current political camps. He has a number of thoughtful ideas about financial-sector reform. He is no libertarian and even proposes a “national bank specializing in extending credit or equity capital to start-up firms”–not my favorite idea.

For the full review, see:

EDWARD GLAESER. “How to Unleash the Economy.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., Oct. 19, 2013): C7.

(Note: ellipses, and bracketed word, added.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date Oct. 18, 2013, and has the title “BOOKSHELF; Book Review: ‘Mass Flourishing’ by Edmund Phelps; Innovative dynamism is the key to economic success and personal satisfaction, a Nobel-winner argues.”)

The book under review is:

Phelps, Edmund S. Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Source of book image: http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/files/2013/08/Mass-Flourishing-cover.jpg

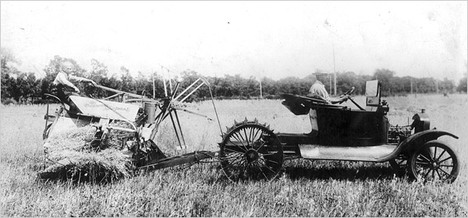

“OFF ROAD; Kits to take the Model T places Henry Ford never intended included tractor conversions, . . . ” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“OFF ROAD; Kits to take the Model T places Henry Ford never intended included tractor conversions, . . . ” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.