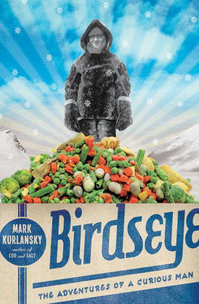

“A computer image shows a rendering of a spacecraft preparing to capture a water-rich, near-Earth asteroid.” Source of caption: print version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. B3) SEATTLE–A start-up with high-profile backers on Tuesday unveiled its plan to send robotic spacecraft to remotely mine asteroids, a highly ambitious effort aimed at opening up a new frontier in space exploration.

At an event at the Seattle Museum of Flight, a group that included former National Aeronautics and Space Administration officials unveiled Planetary Resources Inc. and said it is developing a “low-cost” series of spacecraft to prospect and mine “near-Earth” asteroids for water and metals, and thus bring “the natural resources of space within humanity’s economic sphere of influence.”

The solar system is “full of resources, and we can bring that back to humanity,” said Planetary Resources co-founder Peter Diamandis, who helped start the X-Prize competition to spur nongovernmental space flight.

The company said it expects to launch its first spacecraft to low-Earth orbit–between 100 and 1,000 miles above the Earth’s surface–within two years, in what would be a prelude to sending spacecraft to prospect and mine asteroids.

The company, which was founded three years ago but remained secret until last week, said it could take a decade to finish prospecting, or identifying the best candidates for mining.

For the full story, see:

AMIR EFRATI. “Asteroid-Mining Strategy Is Outlined by a Start-Up.” The Wall Street Journal (Weds., April 25, 2012): B3.

(Note: the online version of the story is dated April 24, 2012, and has the title “Start-Up Outlines Asteroid-Mining Strategy.”)