(p. A13) Like the mythical monster Hydra–who grew two heads every time Hercules cut one off–President Obama, in both his State of the Union address and his new budget, has defiantly doubled down on his brand of industrial policy, the usually ill-advised attempt by governments to promote particular industries, companies and technologies at the expense of broad, evenhanded competition.

Despite his record of picking losers–witness the failed “clean energy” projects Solyndra, Ener1 and Beacon Power–Mr. Obama appears determined to continue pushing his brew of federal spending, regulations, mandates, special waivers, loan guarantees, subsidies and tax breaks for companies he deems worthy.

Favoring key constituencies with taxpayer money appeals to politicians, who can claim to be helping the overall economy, but it usually does far more harm than good. It crowds out valuable competing investment efforts financed by private investors, and it warps decisions by bureaucratic diktats susceptible to political cronyism. Former Obama adviser Larry Summers echoed most economists’ view when he warned the administration against federal loan guarantees to Solyndra, writing in a 2009 email that “the government is a crappy venture capitalist.”

Category: Entrepreneurship

“The Patience of Jobs”

(p. 7) Steve Jobs was missing from the scene of the meeting, though he would soon be Disney’s largest individual shareholder (the acquisition was a stock-for-stock trade) and the newest member of Disney’s board. Lasseter was right about his money; Jobs had driven a hard bargain in buying Lucas’s Computer Division for five million dollars (not ten million, as is sometimes reported), but as it turned out, he put ten times that amount into the company over the course of a decade to keep it afloat. Few other investors would have had the patience of Jobs.

Source:

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

(Note: my strong impression is that the pagination is the same for the 2008 hardback and the 2009 paperback editions, except for part of the epilogue, which is revised and expanded in the paperback. I believe the passage above has the same page number in both editions.)

Nasar Gives Compelling Portrait of Joseph Schumpeter and His Vienna

Source of book image: http://luxuryreading.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/grand-pursuit.jpg

(p. C31) Ms. Nasar gives us Belle Époque Vienna — infatuated with modernity and challenging London in the race to electrify with new telephone service, state-of-the-art factories and power-driven trams — and then a devastating picture of Vienna at the end of World War I: war veterans loitering outside restaurants waiting for scraps, and desperate members of a middle class that saw inflation wipe out all its savings trading a piano for a sack of flour, a gold watch chain for a few sacks of potatoes.

. . .

Among the more compelling portraits in this volume is that of Joseph Alois Schumpeter, the brilliant European economist who argued that the distinctive feature of capitalism was “incessant innovation” — a “perennial gale of creative destruction” — and who identified the entrepreneur as the visionary who could “revolutionize the pattern of production by exploiting an invention” or “an untried technological possibility.”

For the full review, see:

MICHIKO KAKUTANI. “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; The Economist’s Progress: Better Living Through Fiscal Chemistry.” The New York Times (Fri., December 2, 2011): C31.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated December 1, 2011.)

Economic Freedom and Growth Depend on Protecting the Right to Rise

(p. A19) Congressman Paul Ryan recently coined a smart phrase to describe the core concept of economic freedom: “The right to rise.”

Think about it. We talk about the right to free speech, the right to bear arms, the right to assembly. The right to rise doesn’t seem like something we should have to protect.

But we do. We have to make it easier for people to do the things that allow them to rise. We have to let them compete. We need to let people fight for business. We need to let people take risks. We need to let people fail. We need to let people suffer the consequences of bad decisions. And we need to let people enjoy the fruits of good decisions, even good luck.

That is what economic freedom looks like. Freedom to succeed as well as to fail, freedom to do something or nothing. . . .

. . .

But when it comes to economic freedom, we are less forgiving of the cycles of growth and loss, of trial and error, and of failure and success that are part of the realities of the marketplace and life itself.

. . .

. . . , we must choose between the straight line promised by the statists and the jagged line of economic freedom. The straight line of gradual and controlled growth is what the statists promise but can never deliver. The jagged line offers no guarantees but has a powerful record of delivering the most prosperity and the most opportunity to the most people. We cannot possibly know in advance what freedom promises for 312 million individuals. But unless we are willing to explore the jagged line of freedom, we will be stuck with the straight line. And the straight line, it turns out, is a flat line.

For the full commentary, see:

JEB BUSH. “OPINION; Capitalism and the Right to Rise; In freedom lies the risk of failure. But in statism lies the certainty of stagnation.” The Wall Street Journal (Mon., December 19, 2011): A19.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Paul Allen Uses Microsoft Profits for Bold Private Space Project

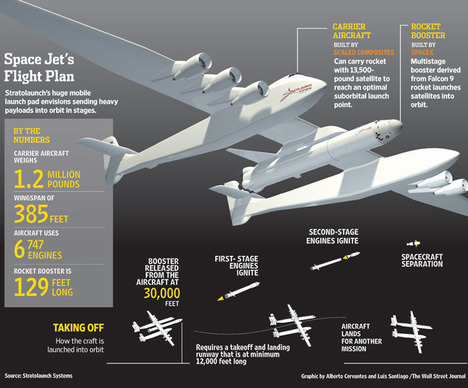

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. B1) Microsoft Corp. co-founder Paul Allen indicated he is prepared to commit $200 million or more of his wealth to build the world’s largest airplane as a mobile platform for launching satellites at low cost, which he believes could transform the space industry.

Announced Tuesday, the novel, high-risk project conceived by renowned aerospace designer Burt Rutan seeks to combine engines, landing gears and other parts removed from old Boeing 747 jets with a newly created composite craft from Mr. Rutan and a powerful rocket to be built by a company run by Internet billionaire and commercial-space pioneer Elon Musk.

Dubbed Stratolaunch and funded by one of Mr. Allen’s closely held entities, the venture seeks to meld decades-old airplane technology with cutting-edge booster-rocket designs in an unprecedented way to assemble a hybrid that would offer the first totally privately funded space transportation system.

“What Success Had Brought Him, . . . , Was Freedom”

(p. 5) The success of Pixar’s films had brought him something exceedingly rare in Hollywood: not the house with the obligatory pool in the backyard and the Oscar statuettes on the fireplace mantel, or the country estate, or the vintage Jaguar roadster–although he had all of those things, too. It wasn’t that he could afford to indulge his affinity for model railroads by acquiring a full-size 1901 steam locomotive, with plans to run it on the future site of his twenty-thousand-square-foot mansion in Sonoma Valley wine country. (Even Walt Dìsney’s backyard train had been a mere one-eighth-scale replica.)

None of these was the truly important fruit of Lasseter’s achievements. What success had brought him, most meaningfully, was freedom. Having created a new genre of film with his colleagues at Pixar, he had been able to make the films he wanted to make, and he was coming back to Disney on his own terms.

Source:

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

(Note: ellipsis in title was added.)

(Note: my strong impression is that the pagination is the same for the 2008 hardback and the 2009 paperback editions, except for part of the epilogue, which is revised and expanded in the paperback. I believe the passage above has the same page number in both editions.)

Pixar as a Case Study on Innovative Entrepreneurship

Source of book image: http://murraylibrary.org/2011/09/the-pixar-touch-the-making-of-a-company/

Toy Story and Finding Nemo are among my all-time-favorite animated movies. How Pixar developed the technology and the story-telling sense, to make these movies is an enjoyable and edifying read.

Along the way, I learned something about entrepreneurship, creative destruction, and the economics of technology. In the next couple of months I occasionally will quote passages that are memorable examples of broader points or that raise thought-provoking questions about how innovation happens.

Book discussed:

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch: The Making of a Company. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Intuit Aimed to End Hassle and Was Mainly Self-Financed at Start

“Scott Cook.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

(p. B4) WSJ: Before building Intuit, you worked at large firms like Procter & Gamble Co. and Bain & Co. What prompted you to leave Corporate America and start your own business?

Mr. Cook: My wife complained about doing the bills. It was a hassle. I had been trained at P&G to find a problem that everybody has and that you could solve with technology. And this struck me as a classic entrepreneurial opportunity. Nobody likes to pay bills. There were about 20-plus personal-finance software products already on the market.

. . .

WSJ: How much start-up capital did have to work with?

Mr. Cook: We raised between $500,000 and $600,000. It came from my savings and my retirement plan that I cashed out. I also borrowed money from my parents. Lines of credit were another big source of capital. The banks were lending to me and my wife as a couple, not the business. We tried venture capital and that failed. We talked to about two dozen venture-capital firms and they all shut us down. We did get two angels to invest, but they put in only $151,000, total.

For the full interview, see:

SARAH E. NEEDLEMAN. “HOW I BUILT IT; For Intuit Co-Founder, the Numbers Add Up” The Wall Street Journal (Thurs., AUGUST 18, 2011): B4.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

Personal Risk Lovers Make Better CEOs?

(p. C4) Chief executives with a penchant for personal risk-taking are also corporate risk-takers who take on more debt, aggressively pursue mergers and acquisitions, and make bold equity plays. But, in general, they are also more effective leaders who create more value in their organizations than their less risk-loving counterparts. And they do so, the researchers add, without additional incentives; they imprint their risk-loving natures on their companies because it’s simply who they are.

For the full summary, see:

DAVID DISALVO. “Management; For Effective CEOs, Look Up.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., August 20, 2011): C4.

The article summarized is:

Cain, Matthew D., and Stephen B. McKeon. “Cleared for Takeoff? CEO Personal Risk-Taking and Corporate Policies.” SSRN eLibrary (2011).

Branson Advises Entrepreneurs: “Think of What Frustrates You”

Source of caricature: online version of the WSJ interview quoted and cited below.

(p. A13) Governments have long dominated space, starting with the Soviet Union’s 1957 launch of Sputnik 1. The U.S. soon followed. “If they’d used just a small fraction of that money as prize money and given it to the best commercial companies, that money would’ve been far better spent,” Mr. Branson muses. “The $10 million [Ansari] X Prize very much sparked our move into space travel,” he notes, referring to the competition organized by entrepreneur Peter Diamandis and launched in 1996.

Mr. Branson had dreamed of exploring the final frontier for decades. “I think it just simply goes back to watching the moon landing on blurry black-and-white television when I was a teenager and thinking, one day I would go to the moon–and then realizing that governments are not interested in us individuals and creating products that enable us to go into space,” he says. In 1995, after making billions of dollars in the music and airline businesses, Mr. Branson registered a new company, Virgin Galactic (the name “sounded good”), at London’s Companies House. Then the company started searching for rocket scientists and the right technology.

Several years later, in July 2002, Virgin’s team traveled to California to check on American aerospace designer Burt Rutan’s progress on the Virgin Atlantic Global Flyer, a plane built “to circumnavigate the globe non-stop on a single tank of fuel,” according to Virgin’s website. Virgin discovered that Mr. Rutan intended to compete for the X Prize with SpaceShip One, the world’s first privately developed spacecraft, financed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

Mr. Branson quickly struck a deal: Virgin would license Mr. Rutan’s SpaceShip One technology from Mr. Allen if he won the competition. In 2004, Mr. Rutan did just that, and Virgin Galactic was off to the races.

. . .

So what advice does Mr. Branson have for aspiring entrepreneurs? “Think of what frustrates you–and if you’re frustrated by something and you feel ‘Dammit, if only people could do this better,’ then go try to do it better yourself. It can start off in a really small way . . . and you’ll be surprised: If you’re doing it better yourself, in whatever field it is, you’ll be filling a gap and you suddenly might start creating a business.”

For the full interview, see:

MARY KISSEL. “THE WEEKEND INTERVIEW with Richard Branson; Space: The Next Business Frontier; By next Christmas the airline mogul could be ferrying paying customers outside the atmosphere–and, later, to the bottom of the ocean.” The Wall Street Journal (Sat., December 17, 2011): A13.

(Note: ellipsis added.)