(p. C1) OHINEWAI, New Zealand — Watching grass grow is supposed to be dull. But watching it grow with a dairy farmer like Malcolm Lumsden is anything but.

Cows turn grass into milk, and while dairy farmers in the United States and Europe rely much more on grain to feed cows, here in New Zealand grass is pretty much all they get. The richer and more abundant the grass, the richer and more abundant the milk.

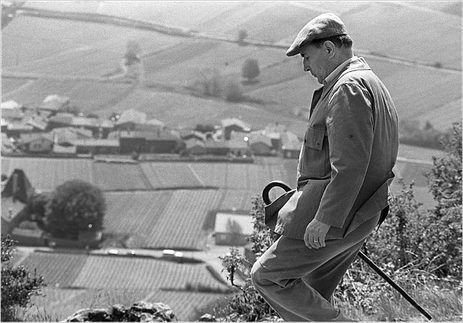

So like mechanics tuning a race car engine, Mr. Lumsden and his fellow dairy farmers keep close track of the weight of the grass in their pastures, precisely measure its protein and sugar content, and produce computer charts tracking how much they have left to feed their cows through winter.

“It’s a science,” Mr. Lumsden mused as he watched a group of his black-and-white Friesians munching dark grass on a wet winter day. “It’s a real science.”

Dairy farming in New Zealand was not always this sophisticated. But ever since a liberal but free-market government swept to power in 1984 and essentially canceled handouts to farmers — something that just about every other government in an advanced industrial nation has considered both politically and economically impossible — agriculture here has never been the same.

The farming community was devastated — but not for long. Today, agriculture remains the lifeblood of New Zealand’s econ-(p. C5)omy. There are still more sheep and cows here than people, their meat, milk and wool providing the country with its biggest source of export earnings. Most farms are still owned by families, but their incomes have recovered and output has soared.

“Farming in New Zealand is now a cold, hard business,” said Mr. Lumsden, who at the time of the farming revolution was president of Federated Farmers in the Waikato region, the heart of New Zealand’s dairy country. “I think we have benefited hugely.”

New Zealand’s farmers are not the only ones convinced that eliminating subsidies, or at least sharply cutting them, is a good idea. As negotiators struggle to revive the failing global trade talks and Congress moves ahead on a new farm bill in the United States, New Zealand and Australia — which also cut subsidies but not as drastically — are being extolled by economists and advocates for poor countries as models for Americans and Europeans to follow.

“They went cold turkey and in the process it was very rough on their farming economy,” said Ray Goldberg, a retired professor of agriculture and business at Harvard Business School. “But they came out healthier and stronger. They proved it could be done.”

Traditional subsidies, economists contend, generally encourage inefficient farmers to grow unprofitable crops far beyond what consumers actually need, secure in the knowledge that the government will help protect them from loss. And they make it much harder for farmers in poor countries to compete on a level playing field against coddled farmers in the West. Removing subsidies, the argument goes, liberates the best farmers anywhere in the world to produce what people really want.

“When you’re not going to get paid for what the market doesn’t want, you have to get off your backside and find out what they want,” said Charlie Pedersen, who, when he is not raising sheep and beef cattle on his farm north of the capital, Wellington, is president of Federated Farmers of New Zealand.

. . .

“What’s happened since the reforms is that you have a new type of farm emerging — a business farm,” Mr. Lumsden said. Giving up subsidies made farming harder, he conceded, but introduced the pride that comes of entrepreneurship. “It made it more enjoyable,” he said.

Source: screen capture from the CNN report cited below.

Source: screen capture from the CNN report cited below. Source: screen capture from the CNN report cited above.

Source: screen capture from the CNN report cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Part of a Greenpeace ad lambasting Senator Edward Kennedy’s opposition to windmills that would effect his view. Source of image of part of ad: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Part of a Greenpeace ad lambasting Senator Edward Kennedy’s opposition to windmills that would effect his view. Source of image of part of ad: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.