Residential plastic pipe. Source of photo: http://www.omaha.com/index.php?u_pg=46

Residential plastic pipe. Source of photo: http://www.omaha.com/index.php?u_pg=46

(p. D1) The City of Omaha is considering allowing an alternative to copper pipes in residential plumbing, a move the local builders association says could keep new home prices from rising so fast.

. . .

(p. D2) "Omaha is kind of unique in not allowing plastic. It’s kind of an isolated pocket," said Blas Hernandez, Papillion’s chief building official, who also has worked in the Kansas City, Denver, upstate New York and central Nebraska areas.

Mike Lipke, western regional manager for FlowGuard Gold CPVC pipes, agreed. He said Omaha and Chicago stand out among Midwestern cities for not allowing plastic water pipes.

Several people with long tenure in the building industry said they believe Omaha has lagged in adoption of plastics because the material is less labor-intensive to install and organized labor has fought to protect work for its members.

Stephen Andersen, business manager for the 470-member Omaha Plumbers Local 16, said he doesn’t think it’s necessarily faster to install plastic pipes, and he personally favors copper "because it’s such a good product, a proven product."

. . .

With the housing market slowed and copper prices still high, now may be the time to make affordability the most important consideration, said Paul Frazier, president of the Frazier Co. and a member of the Metro Omaha Builders Association’s board.

"MOBA is fully behind" the proposed change, President Rocky Goodwin said. Frazier represented MOBA in discussions with the Omaha Plumbing Board.

"We’re long overdue for this," Frazier said. "Anything that holds costs down while doing as good or better job is a good thing.

. . .

Lipke, who sells CPVC, said all the model codes and all 50 states approve the use of plastic and plastic has captured two-thirds of the market.

. . .

"People might try it because it’s less money, but they won’t keep using it if it doesn’t work," Lipke said. "It’s a good product, and it certainly shouldn’t be banned the way it is in Omaha."

For the full story, see:

(Note: ellipses added.)

[Joseph Schumpeter was born on February 8, 1883.]

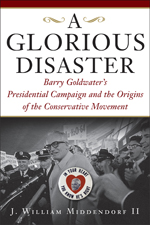

Source of book image:

Source of book image:

Dr. John Snow. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Dr. John Snow. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above. Edwin Chadwick. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above.

Edwin Chadwick. Source of photo: online version of the WSJ article cited above. Barney Frank. Source of photo:

Barney Frank. Source of photo:  CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.

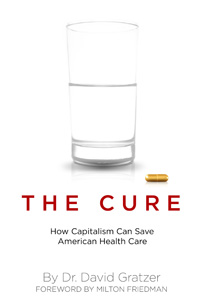

CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below. Source of book image:

Source of book image:

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.