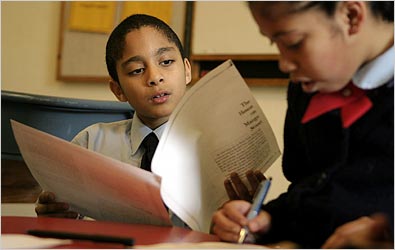

A Bangalore radiologist. One of three radiologists in India known to be reading U.S. scans. Each of the three has a U.S. degree, as required by U.S. law. Source of image: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/19/business/19leonhardt.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

A Bangalore radiologist. One of three radiologists in India known to be reading U.S. scans. Each of the three has a U.S. degree, as required by U.S. law. Source of image: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/19/business/19leonhardt.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

(p. C1) Radiologists seem like just the sort of workers who should be scared. Computer networks can now send an electronic image to India faster than a messenger can take it from one hospital floor to another. Often, those images are taken during emergencies at night, when radiologists here are sleeping and radiologists in India are not.

There also happens to be a shortage of radiologists in the United States. Sophisticated new M.R.I. and CT machines can detect tiny tumors that once would have gone unnoticed, and doctors are ordering a lot more scans as a result.

When I talked this week to E. Stephen Amis Jr., the head of the radiology department at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, he had just finished looking at some of the 700 images that had been produced by a single abdominal CT exam. "We were just taking pictures of big, thick slabs of the body 20 years ago," Dr. Amis said. "Now we’re taking thinner and thinner slices."

Economically, in other words, ra-(p. C6)diology has a lot in common with industries that are outsourcing jobs. It has high labor costs, it’s growing rapidly and it’s portable.

Politically, though, radiology could not be more different. Unlike software engineers, textile workers or credit card customer service employees, doctors have enough political power to erect trade barriers, and they have built some very effective ones.

To practice medicine in this country, doctors are generally required to have done their training here. Otherwise, it is extremely difficult to be certified by a board of other doctors or be licensed by a state government. The three radiologists Mr. Levy found in Bangalore did their residencies at Baylor, Yale and the University of Massachusetts before returning home to India.

"No profession I know of has as much power to self-regulate as doctors do," Mr. Levy said.

So even if the world’s most talented radiologist happened to have trained in India, there would be no test he could take to prove his mettle here. It’s as if the law required cars sold here to have been made by the graduates of an American high school.

Much as the United Automobile Workers might love such a law, Americans would never tolerate it, because it would drive up the price of cars and keep us from enjoying innovations that happened to come from overseas. But isn’t that precisely what health care protectionism does? It keeps out competition.

For the full story, see:

Leonhardt, David. "Political Clout in the Age of Outsourcing." The New York Times (Weds., April 19, 2006): C1 & C4.

Source of book image:

Source of book image: