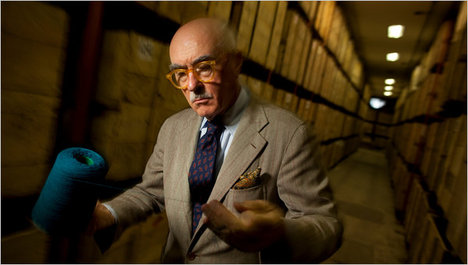

“Carlo Altomonte, an economist, says that “Italy’s problem isn’t that we have a lot of debt. It’s that we don’t grow.”” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Carlo Altomonte, an economist, says that “Italy’s problem isn’t that we have a lot of debt. It’s that we don’t grow.”” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. 6) “I know that in the States, all Mediterranean countries get lumped together,” says Carlo Altomonte, an economist with Bocconi University in Milan. “But Italy’s problem isn’t that we have a lot of debt. It’s that we don’t grow.”

. . .

“There is no sense of what a market economy is in this country,” says Professor Altomonte. “What you see here is an incredible fear of competition.”

. . .

FIVE years ago, Francesco Giavazzi needed a taxi. Cabs are relatively scarce in Milan, especially at 5 a.m., when he wanted to head to the airport, so he called a company at 4:30 to schedule a pickup. But when he climbed into the cab half an hour later, he discovered that the meter had been running for more than 20 minutes, because the taxi driver had arrived soon after the call and started charging for (p. 7) his time. Allowed by the rules, but to Mr. Giavazzi, utterly unfair.

“So it was 20 euros before we started the trip to the airport,” recalls Mr. Giavazzi, who is an economics professor at Bocconi University. “I said, ‘This is impossible.’ ”

Professor Giavazzi later wrote an op-ed article denouncing this episode as another example of the toll exacted by Italy’s innumerable guilds, known by several names here, including “associazioni di categoria.” (These are different from unions, another force here, in that guilds are made up of independent players in a trade or profession who have joined to keep outsiders out and maintain standards, as opposed to representing employees in negotiations with management, as a union might.) Even baby sitters have associations in Italy.

The op-ed did not endear Professor Giavazzi to the city’s cab drivers. They pinned leaflets with his name and address at taxi stands around Milan and for the next five nights, cabs drove around his home, honking their horns.

“This is a country with a lot of rents,” says Professor Giavazzi, sitting in his office one recent afternoon, . . . “You need a notary public, it’s like 1,000 euros before you even open your mouth. If you’re a notary public in this country, you live like a king.”

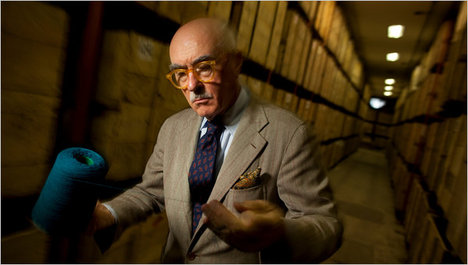

For Mr. Barbera, as is true with every entrepreneur here, the prevalence and power of Italy’s guilds explains much of what is driving up costs. He says he must overspend for accountants, lawyers, truckers and other members of guilds on a list that goes on and on: “Everything has a tariff, and you have to pay.”

. . .

Italians, notes Professor Altomonte, are among the world’s heaviest consumers of bottled water. “Do you know why? Because the water in the tap comes from the government.”

The suspicion of Italians when it comes to extra-familial institutions explains why many here care more about protecting what they have than enhancing their wealth. Most Italians live less than a mile or two from their parents and stay there, often for financial benefits like cash and in-kind services like day care. It’s an insularity that runs all the way up to the corporate suites. The first goal of many entrepreneurs here isn’t growth, so much as keeping the business in the family. For a company to really expand, it needs capital, but that means giving up at least some control. So thousands of companies here remain stubbornly small — all of which means Italy is a haven for artisans but is in a lousy position to play the global domination game.

“The prevailing management style in this country is built around loyalty, not performance,” says Tito Boeri, scientific director at Fondazione Rodolfo Debenedetti, who has written about Italy’s dynastic capitalism.

For the full story, see:

DAVID SEGAL. “Is Italy Too Italian?” The New York Times (Sun., August 1, 2010): 1 & 6-7.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated July 31, 2010.)

“The clothier Luciano Barbera in his family’s “spa for yarn,” where crates of thread rest for months. Economists fear that such small-scale artisanship cannot sustain Italy’s economy forever.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“The clothier Luciano Barbera in his family’s “spa for yarn,” where crates of thread rest for months. Economists fear that such small-scale artisanship cannot sustain Italy’s economy forever.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.