A non-federally-chartered taxi leaves the Cancun Hilton, headed for the Cancun airport, charging $23. An identical, but federally-chartered cab, making the reverse trip, charges $40. (Photo by Art Diamond.)

A non-federally-chartered taxi leaves the Cancun Hilton, headed for the Cancun airport, charging $23. An identical, but federally-chartered cab, making the reverse trip, charges $40. (Photo by Art Diamond.)

When we arrived at the Cancun airport we faced a chaotic environment where many Mexicans were yelling at us to buy taxi tickets. After buying a ticket for $40, someone escorted us to a crowded, chaotic place to wait for a cab. We waited and waited in the noise and the heat. At some point, my daughter Jenny commented, "These people need to get organized."

Yes, Jenny they sure do! And you might think that what they need in order to get organized, is for the government to come in to organize them.

But it turns out that the government has already come in. Only federally charged taxis are allowed to take passengers from the airport to the hotel zone. The price is fixed at $40. On the other hand, any taxi may take passengers back to the airport, from the hotel zone. The base price for a return trip was $23 . (I added a $2 tip out of sympathy for the cabbie not driving a federally anointed cab.)

So, yes, these people need to get organized, and the best way to do that is to get their government out of their way, so that they can organize themselves through the free market.

Note: relevant guide book passage: "[Returning to the airport] the rate will be much less for the trip from the airport. (Only federally chartered taxis may take fared from the airport, but any taxi may bring passengers to the airport.)" (p. 78)

Note: italics in original; bracketed phrase added.

Source:

Baird, David, and Lynne Bairstow. Frommer’s Cancun, Cozumel & the Yucatan 2007. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing, Inc., 2006.

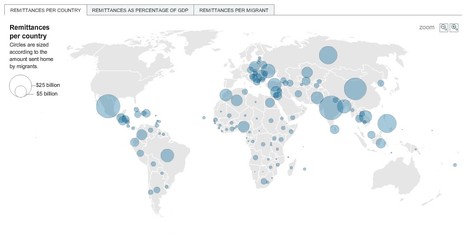

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from: