Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/customer-reviews/0385479492/ref=cm_cr_dp_2_1/104-0758544-2447945?%5Fencoding=UTF8&customer-reviews.sort%5Fby=-SubmissionDate&n=283155

Source of book image: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/customer-reviews/0385479492/ref=cm_cr_dp_2_1/104-0758544-2447945?%5Fencoding=UTF8&customer-reviews.sort%5Fby=-SubmissionDate&n=283155

Co-opetition is a readable book with some plausible discussion of interesting cases. The central message is that business is not always a zero-sum game (in contrast, say, to competitive sports). One implication is that the firm’s complementary relationships with other firms, may deserve as much attention as its competitive relationships.

One qualitfication: I think the book too much emphasizes game theory as the sine qua non source of the book’s insights. About the only game theory you really need to understand 99% of the book’s analysis is the concept of the "zero-sum game."

In a couple of places, the book discusses "leapfrog" competiton in the video game industry:

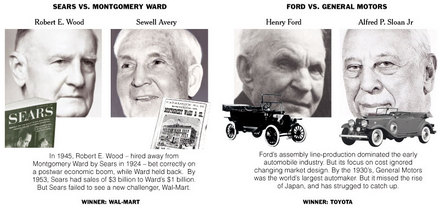

(p. 102) By mid-1995 the price of the 3DO machine was down to $400 (with $150 worth of software thrown in). Cumulative sales passed half a million. Progress, surely, but as of early 1996, 3DO’s future remains uncertain. It no longer has the 32-bit game to itself. Sega is shipping its 32-bit Saturn machine at $400. Sony has launched its 32-bit PlayStation at $300. Looking to leapfrog them all is Nintendo, whose 64-bit Ultra machine is due out in April 1996 at a price under $250.

(p. 114) Could a challenger hope to breach Nintendo’s virtuous circle? Not once the circle had got rolling. Forget about alternatives–TV, books, sports. From a kid’s perspective, there were no good alternatives to a video game. The only real threat came from alternative video game systems. Here, software was key, as always. With a huge library of Nintendo titles to choose from, why would anyone buy another machine? Perhaps a challenger could take successful Nintendo games over to its platform and then offer its own library. But the exclusivity clause killed that option. No game could be taken to another platform for a two-year period, by which time the game was passe. A challenger would have had to start from scratch. While large profits and shortages normally invite entry, the virtuous circle made competing in Nintendo’s game hopeless. The only hope was to leapfrog Nintendo with a new technology; that’s what Sega ultimately did, as we’ll see in the Scope chapter.

Source:

Brandenburger, Adam M., and Barry J. Nalebuff. Co-Opetition; a Revolution Mindset That Combines Competition and Cooperation; the Game Theory Strategy That’s Changing the Game of Business, 1st ed. Currency, 1996.

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Charles Koch. Source of image: online version of WSJ article cited below.