(p. D3) . . . after a trip to Israel for his sister’s bat mitzvah, Jack Millman came back to New York wondering whether the higher costs of kosher foods were justified.

“Most consumers perceive of kosher foods as being healthier or cleaner or somehow more valuable than conventional foods, and I was interested in whether they were in fact getting what they were paying for,” said Mr. Millman, 18 and a senior at the Horace Mann School in New York City.

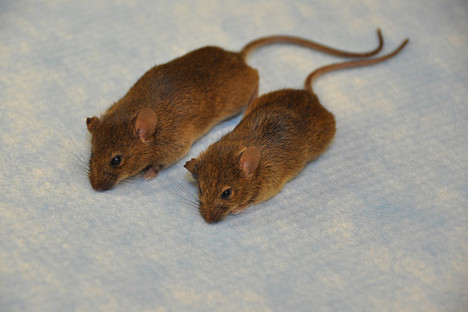

That question started him on a yearlong research project to compare the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli bacteria on four types of chickens: those raised conventionally; organically; without antibiotics, and those slaughtered under kosher rules. “Every other week for 10 weeks, I would go and spend the entire Saturday buying chicken,” he said. “We had it specifically mapped out, and we would buy it and put it on ice in industrial-strength coolers given to us by the lab, and ship it out.”

All told, Mr. Millman and his mother, Ann Marks, gathered 213 samples of chicken drumsticks from supermarkets, butcher shops and specialty stores in the New York area.

Now they and several scientists have published a study based on the project in the journal F1000 Research. The results were surprising.

Kosher chicken samples that tested positive for antibiotic-resistant E. coli had nearly twice as much of the bacteria as the samples from conventionally raised birds did. And even the samples from organically raised chickens and those raised without antibiotics did not significantly differ from the conventional ones.

For the full story, see:

STEPHANIE STROM. “A Science Project With Legs.” The New York Times (Tues., November 5, 2013): D3.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

(Note: the online version of the story has the date November 4, 2013.)

The academic article on E. coli in different types of chicken, is:

Millman, Jack M., Kara Waits, Heidi Grande, Ann R. Marks, Jane C. Marks, Lance B. Price, and Bruce A. Hungate. “Prevalence of Antibiotic-Resistant E. Coli in Retail Chicken: Comparing Conventional, Organic, Kosher, and Raised without Antibiotics.” F1000Research 2 (2013).