Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graph: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

The article quoted below suggests that an important new “disruptive” memory technology may be on the horizon. It sounds as though it would be what economists call a “general purpose technology” that would be useful in generating a large number of innovative applications.

(My guess is that in Christensen’s terminology, this technology would be more sustaining, than disruptive, since the technology seems as though it would be of immediate interest to the mainstream market.)

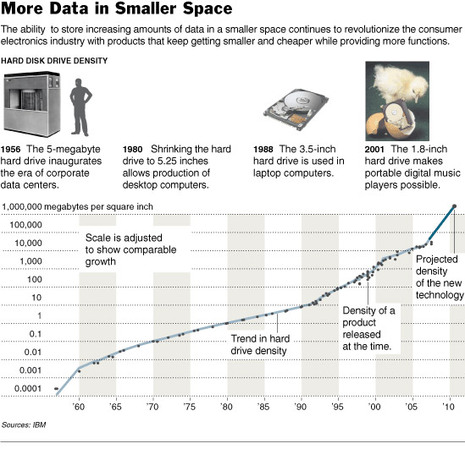

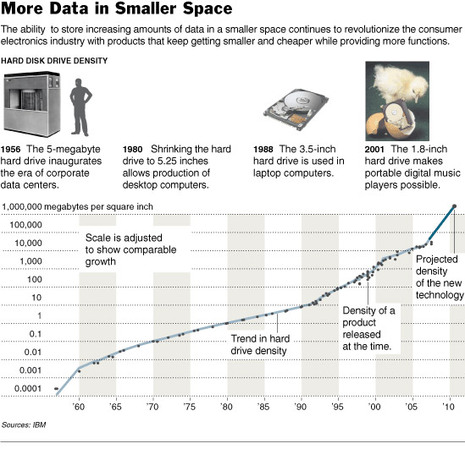

(p. C1) SAN JOSE, Calif. — The ability to cram more data into less space on a memory chip or a hard drive has been the crucial force propelling consumer electronics companies to make ever smaller devices.

It shrank the mainframe computer to fit on the desktop, shrank it again to fit on our laps and again to fit into our shirt pockets.

. . .

Mr. Parkin thinks he is poised to bring about another breakthrough that could increase the amount of data stored on a chip or a hard drive by a factor of a hundred. If he proves successful in his quest, he will create a “universal” computer memory, one that can potentially replace dynamic random access memory, or DRAM, and flash memory chips, and even make a “disk drive on a chip” possible.

. . .

(p. C8) Mr. Parkin’s new approach, referred to as “racetrack memory,” could outpace both solid-state flash memory chips as well as computer hard disks, making it a technology that could transform not only the storage business but the entire computing industry.

“Finally, after all these years, we’re reaching fundamental physics limits,” he said. “Racetrack says we’re going to break those scaling rules by going into the third dimension.”

His idea is to stand billions of ultrafine wire loops around the edge of a silicon chip — hence the name racetrack — and use electric current to slide infinitesimally small magnets up and down along each of the wires to be read and written as digital ones and zeros.

. . .

Mr. Parkin said he had recently shifted his focus and now thought that his racetracks might be competitive with other storage technologies even if they were laid horizontally on a silicon chip.

I.B.M. executives are cautious about the timing of the commercial introduction of the technology. But ultimately, the technology may have even more dramatic implications than just smaller music players or wristwatch TVs, said Mark Dean, vice president for systems at I.B.M. Research.

“Something along these lines will be very disruptive,” he said. “It will not only change the way we look at storage, but it could change the way we look at processing information. We’re moving into a world that is more data-centric than computing-centric.”

This is just a hint, but it suggests that I.B.M. may think that racetrack memory could blur the line between storage and computing, providing a key to a new way to search for data, as well as store and retrieve data.

And if it is, Mr. Parkin’s experimental physics lab will have transformed the computing world yet again.

For the full story, see:

JOHN MARKOFF. “Redefining the Architecture of Memory.” The New York Times (Tues., September 11, 2007): C1 & C8.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Of the two photos at the bottom of the entry, the first is of Stuart S. P. Parkin’s lab at I.B.M, and the second is of Parkin in the lab. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Of the two photos at the bottom of the entry, the first is of Stuart S. P. Parkin’s lab at I.B.M, and the second is of Parkin in the lab. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

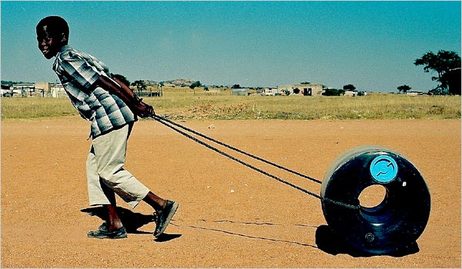

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.