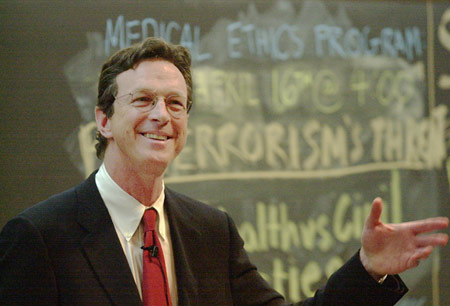

“Colonel Moelmann, a retired Air Force officer, sold seats for $50, but had to spend almost $120,000 of his own to perform.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Colonel Moelmann, a retired Air Force officer, sold seats for $50, but had to spend almost $120,000 of his own to perform.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

I do not share Colonel Moelmann’s particular dream, but I do salute him for paying for his dream himself, rather than trying to force taxpayers to finance it, as so many do in pursuit of their dreams.

(p. A18) Col. Jack Moelmann, a retired Air Force officer from O’Fallon, Ill., blew $118,182.44 on a one-night stand in New York on Saturday. It was everything he had dreamed of, and more: three hours with the mightiest of the mighty Wurlitzers, the legendary pipe organ at Radio City Music Hall.

The experience left him sweaty and exhausted — having your way with a mechanical marvel that contains more than a million parts is hard work — and it reduced his net worth to “the mid-five figures,” he said. But Colonel Moelmann had no regrets. He soldiered through tune after tune, from “The Trolley Song” from “Meet Me in St. Louis” to patriotic songs like “America the Beautiful,” “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Which, as he pointed out before he climbed onto the bench of the giant ebony console at the left-hand edge of the Rockettes’ high-kicking home, guaranteed him a standing ovation.

. . .

“Not many people get their name on the marquee,” he said.

Not many people spend a large chunk of their life savings to buy their way in, either.

The idea for a Radio City concert began with the president of the year-old Theater Organ Society International, the Rev. Gus L. Franklin, and Mr. Page, a member. “We turned our pockets inside out and said, ‘It’s not going to happen,’ ” Mr. Page said.

Colonel Moelmann, the society’s secretary, decided to make it happen — “I looked in the mirror and said: ‘Jack, you have a dream. Go for it.’ “– even though, he said, it was a foregone conclusion that “we’re going to lose money big time.”

He and the organ society put the price of the tickets at $50 a seat, but the show was far from a sellout. Even with the three balconies closed, the orchestra level was about a third full.

Some in the audience were Moelmann fans from way back. Susan Conrad Wells, a law librarian from Granby, Mass., said she had met Colonel Moelmann through an organ club in 1967, when he was stationed in Massachusetts.

Colonel Moelmann said that playing at Radio City presented its own challenges. “You can’t listen to what you’re playing,” he said. “If you listen note by note, once you’ve hit the note and you hear it, it’s too late to say, ‘Oops, I hit the wrong note.’ ”

In the end, he got his standing ovation.

For the full story, see:

JAMES BARRON. “Organist Rents Radio City to Play, Fulfilling Wish.” The New York Times (Mon., August 11, 2008): A18. (B4 in NY edition)

(Note: ellipsis added.)

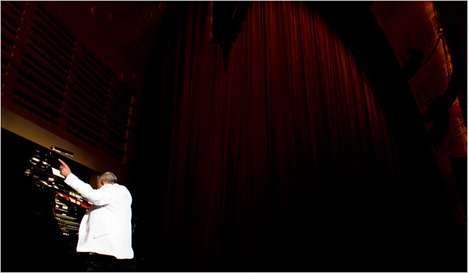

“Jack Moelmann always wanted to play Radio City’s pipe organ, above, even after playing at Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Jack Moelmann always wanted to play Radio City’s pipe organ, above, even after playing at Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.