A week or so ago my mother and I were sharing our disappointment at the firing of Donald Rumsfeld, who we both thought was a good man. She told me that she had thought he would have made a good President. I told her that she was in good company, because in his memoirs, Milton Friedman had expressed the same thought (p. 391).

We were in very good company while Milton Friedman was with us, and I feel a sense of loss, both personally, and for the broader world.

By chance, I sat behind Milton Friedman, and his wife and son, at the Rockefeller Chapel memorial service to honor Milton Friedman’s good friend George Stigler. I can’t remember if Friedman spoke it at the service, or wrote it later, but I remember him saying (or writing) that the world was a darker place without Stigler in it.

And it is darker yet, without Friedman in it. (It is reported that he died of heart failure sometime early this morning at the age of 94.)

My first memory of meeting Milton Friedman was in the early 1970s at Wabash College. My Wabash professor, Ben Rogge, was a friend of Friedman’s. They attended Mount Pelerin Society meetings together, and Rogge, along with his senior colleague John van Sickle, had invited Friedman to deliver a series of lectures at Wabash College, that became the basis of what remains Friedman’s meatiest defense of freedom: Capitalism and Freedom. (Free to Choose is better known, broader, and important, but Capitalism and Freedom is more densely packed with stimulating argument, and provocative new ideas.)

The members of the small, libertarian Van Sickle Club were gathered around Friedman in a lounge at Wabash, and I remember Rogge asking Friedman: ‘If there was a button sitting in front of you, that would instantly abolish the Food and Drug Administration, would you push it?’ I remember Friedman smiling his incredibly delighted smile, and saying simply, with gusto: "yes!"

I remember attending some meetings at the University of Chicago, I think the first History of Economics Society meetings, with Rogge in attendance. (This was in my first couple of years as a Chicago graduate student, when I was mainly doing philosophy.) Stigler invited Rogge up for a drink, and Rogge said said ‘sure’ as long as Diamond could come along. (E.G. West, the Adam Smith biographer, was also there, I think at Rogge’s behest.) The apartment had been Milton Friedman’s for many years. In fact I think he had built the several story apartment building, because he wanted convenient, comfortable living quarters close to his Chicago office. Friedman’s apartment occupied the top floor, and I vaguely recall, afforded a nice view of the campus.

I lived for a year at International House, next to the Friedman apartment building. I remember on Sunday morning’s seeing Friedman dash into International House to buy his copy of the Sunday New York Times. ("Dash" is too strong, but he certainly moved with more vigor than I ever have on Sunday mornings.)

When Friedman left Chicago for the Hoover Institute in California, he sold, or sublet his apartment to Stigler, who apparently used it on evenings when he did not want to drive out to his modest home in the Chicago suburb of Flossmoor.

I was stunned to be in the presence of Stigler in Milton Friedman’s former abode. (I seem to remember E.G. West seeming almost equally overwhelmed.) I remember much of the time being spent with Stigler trying to convince Rogge to join him for golf the following day. Rogge demurred because he was wanting to see, for the first time, I think, a newly born grandchild in the Chicago area. (Family was extremely important to Rogge, both in theory, and in practice.)

I also remember Stigler asking Rogge about Rogge’s having convinced Friedman to give a speech at a fund-raiser at Wabash. Stigler said something to the effect that this was the level of favor that he could not ask often of Friedman, and did the cause really justify it. (I think one of Stigler’s sons had been a Wabash student while Rogge was Dean of Students at Wabash.) Rogge seemed to appreciate Stigler’s point, but seemed to believe that solidifying Wabash’s endowment was a worthy enough cause.

(This, by the way, is ironic, since Rogge agreed with Adam Smith that endowments were apt to be used for purposes different from the donor’s intent. In the founding of Liberty Fund, Rogge had tried to persuade Pierre Goodrich to have the Fund spend all of its funds in some modestly finite number of years.)

After I gradually made the switch from philosophy to economics, at Chicago, I got to know Stigler fairly well, but unfortunately did not know Friedman, personally, as well.

I remember attending a reception at Chicago in honor of Friedman’s winning the Nobel Prize in 1976. (It was at that reception, that I first struck up a conversation with my good friend Luis Locay.)

I registered for Milton Friedman’s price theory class the final time he taught it, I think. It was in a large, dark tiered classroom. At the beginning of every class, Friedman would almost bounce into the classroom, bursting with pent-up energy. I do not smile easily, or often, but I always smiled when I saw Friedman. There was so much good-will, joy in life, enthusiasm for ideas.

During one of these entrances, I noticed that Friedman, well into his 60s, was wearing the counter-culture-popular ‘earth shoes’; apparently he was out-front in footwear, as well as ideas.

One characteristic that came through in class, as well as in his public debates and interviews, was that he was focused on the ideas and not the personalities expressing them. I remember seeing Friedman debating some union official on television. He talked at one point about how he and the official had had to work hard in their youth. Friedman seemed to like the union official; he just disagreed with some of his ideas, and wanted the union official and everyone else, to understand why. By the end of the "debate", the union official had a warm, amused, expression on his face.

I remember once Friedman saying that more of us should speak out more often on more topics; that the bad consequences to us weren’t as bad as we supposed. Probably he was right; though he had a lot working in his favor—his quick-wittedness, his good will, his sense of humor, and probably his being so short in physical stature—it was probably hard for anyone to feel threatened by him, so they were more apt to let down their guard and listen to what he had to say.

One of the unfair hardships of some of Friedman’s years at Chicago, was the constant harassment from a group of Marxist students called, I think, the Spartacus Youth League. Whenever Friedman was scheduled to speak, they would disrupt the event, and try to prevent his speaking.

So when it was time to tape the discussion half-hours of each hour episode of the original "Free to Choose" series, the discussions were scheduled as invitation-only. I was in the audience for two or three of the discussions. (They were fine, but personally, I would have preferred another half hour of pure Friedman.)

As a poor graduate student, I counted myself extremely lucky to find an auto-repairman who was a wizard at finding creative ways to keep old cars running, at low repair cost. He was a man of few words, put he kept the words he gave.

I ran into him and his wife in a little Lebanese restaurant that was run out of the secondary student union just down from I-House. He invited me to sit with them, which I did. I remember him telling me that they were gypsies, and him mentioning that people sometimes had the wrong idea about gypsies. He told me that he had been rais

ed never to go into debt. He told me how cheap White Castle hamburgers used to be. When I told him that I was studying economics, he surprised me by saying that Milton Friedman had been a customer of his, and that he really liked Milton Friedman.

This gypsy was a simple, decent, hard-working fellow. I don’t know, but I strongly guess that Friedman saw the good in this fellow, and treasured what he saw. And the gypsy liked Milton Friedman back.

Whenever I saw Friedman interviewed on television, or read one of his letters, or op-ed pieces, in the Wall Street Journal, I would feel a bit more optimistic about freedom, and life. A lot of people give up, at some point, but Friedman never did—he just kept on observing, and thinking, and speaking. The last time I had any interaction with him was at the meetings of the Association of Private Enterprise Education (APEE) on April 4, 2005. He was hooked up with the conference via video camera from an office in California. He gave a brief presentation, and then spent quite some time answering questions. (I recorded some of these in grainy, small video clips that can be viewed on my web site, or viewed on the web site of the APEE.)

I asked him a question about whether he agreed with Stigler in Stigler’s memoirs that Schumpeter had something important to say about competition. I wasn’t as impressed by his answer to this question, as I was to some of his other answers.

I think that Schumpeter may be remembered as a crucial economist for our understanding of the process of capitalism: innovative new products through creative destruction. But if capitalist innovation prospers, part of the credit will belong to Milton Friedman.

Friedman and Stigler were led into economics in part because of the challenge to capitalism posed by the Great Depression. If depressions of that magnitude were an essential part of what capitalism was about, then a lot of people would prefer to have nothing to do with capitalism. Schumpeter’s response basically was to say that every once in awhile, really bad depressions will happen as part of the process of capitalism, and we just have to suck it up, and live through them.

One of Milton Friedman’s major contributions to economics, was to show that ill-advised government policies, such as a contraction of the money supply, were responsible for making the depression much deeper, and much longer than it needed to have been. (See, e.g, A Monetary History of the United States.)

In other words, he showed that Great Depressions are not an inescapable price we must pay if we choose to embrace the economic freedom, and the creative destruction, of capitalism.

When Friedman cleaned out his Chicago office to head for California, he left in the hallway for scavenging, extra copies of some of his books, and offprints of articles various academics had sent him. So I have a Spanish copy of Capitalism and Freedom (even though I don’t read Spanish), and several offprints of articles from distinguished economists who sent "best wishes" to "Milton."

After the office was cleared out, I remember sticking my head in, and looking around the empty office, one final time, for sentiment’s sake. I was stunned to see a bright red, white and blue silk banner left hanging on the wall. It was festooned with American flags, and said, in large letters: "Buy American!"

I felt anxious and confused: was one of my heroes inconsistent on such a basic issue? So I entered the office, and went over to the banner, and examined it more carefully. It was then that I noticed, in small letters at the bottom of the banner: "Made in Japan".

Some book references relevant to the discussion above:

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, Nber Studies in Business Cycles. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

Friedman, Milton, and Rose D. Friedman. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1980.

Stigler, George J. Memoirs of an Unregulated Economist. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1988.

West, E. G. Adam Smith: The Man and His Works: Arlington House, 1969.

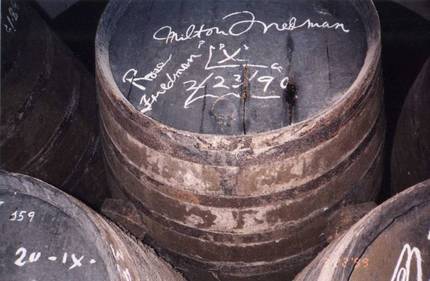

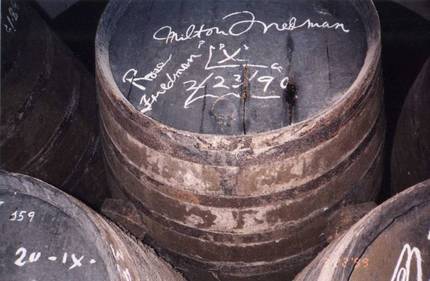

In vino veritas. Photo from Tio Pepe Bodega, Jerez, Spain. Photographer: Dagny Diamond.

In vino veritas. Photo from Tio Pepe Bodega, Jerez, Spain. Photographer: Dagny Diamond.

Continue reading “Milton Friedman, Freedom’s Friend, RIP”

Harvard Medical School antiaging researcher Dr. David Sinclair. Source of image:

Harvard Medical School antiaging researcher Dr. David Sinclair. Source of image:  Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.