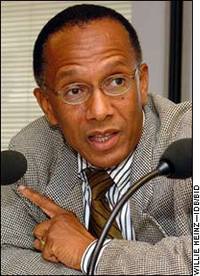

Harvard sociology professor Orlando Patterson. Source of image: http://www.iadb.org/idbamerica/index.cfm?thisid=681

Harvard sociology professor Orlando Patterson. Source of image: http://www.iadb.org/idbamerica/index.cfm?thisid=681

Cambridge, Mass. – Several recent studies have garnered wide attention for reconfirming the tragic disconnection of millions of black youths from the American mainstream. But they also highlighted another crisis: the failure of social scientists to adequately explain the problem, and their inability to come up with any effective strategy to deal with it.

The main cause for this shortcoming is a deep-seated dogma that has prevailed in social science and policy circles since the mid-1960’s: the rejection of any explanation that invokes a group’s cultural attributes — its distinctive attitudes, values and predispositions, and the resulting behavior of its members — and the relentless preference for relying on structural factors like low incomes, joblessness, poor schools and bad housing.

Harry Holzer, an economist at Georgetown University and a co-author of one of the recent studies, typifies this attitude. Joblessness, he feels, is due to largely weak schooling, a lack of reading and math skills at a time when such skills are increasingly required even for blue-collar jobs, and the poverty of black neighborhoods. Unable to find jobs, he claims, black males turn to illegal activities, especially the drug trade and chronic drug use, and often end up in prison. He also criticizes the practice of withholding child-support payments from the wages of absentee fathers who do find jobs, telling The Times that to these men, such levies ”amount to a tax on earnings.”

His conclusions are shared by scholars like Ronald B. Mincy of Columbia, the author of a study called ”Black Males Left Behind,” and Gary Orfield of Harvard, who asserts that America is ”pumping out boys with no honest alternative.”

This is all standard explanatory fare. And, as usual, it fails to answer the important questions. Why are young black men doing so poorly in school that they lack basic literacy and math skills? These scholars must know that countless studies by educational experts, going all the way back to the landmark report by James Coleman of Johns Hopkins University in 1966, have found that poor schools, per se, do not explain why after 10 years of education a young man remains illiterate.

Nor have studies explained why, if someone cannot get a job, he turns to crime and drug abuse. One does not imply the other. Joblessness is rampant in Latin America and India, but the mass of the populations does not turn to crime.

And why do so many young unemployed black men have children — several of them — which they have no resources or intention to support? And why, finally, do they murder each other at nine times the rate of white youths?

. . .

So what are some of the cultural factors that explain the sorry state of young black men? They aren’t always obvious. Sociological investigation has found, in fact, that one popular explanation — that black children who do well are derided by fellow blacks for ”acting white” — turns out to be largely false, except for those attending a minority of mixed-race schools.

An anecdote helps explain why: Several years ago, one of my students went back to her high school to find out why it was that almost all the black girls graduated and went to college whereas nearly all the black boys either failed to graduate or did not go on to college. Distressingly, she found that all the black boys knew the consequences of not graduating and going on to college (”We’re not stupid!” they told her indignantly).

So why were they flunking out? Their candid answer was that what sociologists call the ”cool-pose culture” of young black men was simply too gratifying to give up. For these young men, it was almost like a drug, hanging out on the street after school, shopping and dressing sharply, sexual conquests, party drugs, hip-hop music and culture, the fact that almost all the superstar athletes and a great many of the nation’s best entertainers were black.

Not only was living this subculture immensely fulfilling, the boys said, it also brought them a great deal of respect from white youths. This also explains the otherwise puzzling finding by social psychologists that young black men and women tend to have the highest levels of self-esteem of all ethnic groups, and that their self-image is independent of how badly they were doing in school.

I call this the Dionysian trap for young black men. The important thing to note about the subculture that ensnares them is that it is not disconnected from the mainstream culture. To the contrary, it has powerful support from some of America’s largest corporations. Hip-hop, professional basketball and homeboy fashions are as American as cherry pie. Young white Americans are very much into these things, but selectively; they know when it is time to turn off Fifty Cent and get out the SAT prep book.

For young black men, however, that culture is all there is — or so they think. Sadly, their complete engagement in this part of the American cultural mainstream, which they created and which feeds their pride and self-respect, is a major factor in their disconnection from the socioeconomic mainstream.

For the full commentary, see: