"Dr. Steven Meed works for Sickday Medical House Calls, a service in Manhattan." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"Dr. Steven Meed works for Sickday Medical House Calls, a service in Manhattan." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“We have that perfect storm. The current system doesn’t work well for patients or physicians,” said Dr. Rick Kellerman, a doctor who works in Wichita, Kan., and is president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. "More doctors are coming up with new home business practice models. They’re exasperated with paperwork and insurance regulation.”

The demand for primary care physicians outweighs the supply in many cities, so patients can wait weeks, and even months, for appointments, and hospital emergency rooms are becoming overloaded with nonemergency cases. Health insurance premiums, meanwhile, have continued to rise.

Some doctors are doing things like taking only house-call appointments or operating “micropractices” in which they work without front-office staff and nurses and see their patients in a smaller one-room office, Dr. Kellerman said.

When making house calls, “you get paid,” said Dr. Steven Meed, one of eight New York physicians working for Sickday Medical House Calls, which started last year and serves patients in Manhattan. “The paperwork overhead is kept at a minimum, the fee is fixed and it’s not going to be reduced.”

For the full story, see:

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

"He took the subway, top, to travel to the apartment of a patient, Kayla McDermott, who had a sore throat." Source of caption and photos: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Sally Satel is a medical doctor and a resident scholar at the Amerrican Enterprise Institute. Source of photo:

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of maps: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

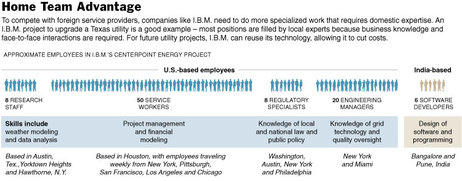

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:  Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.

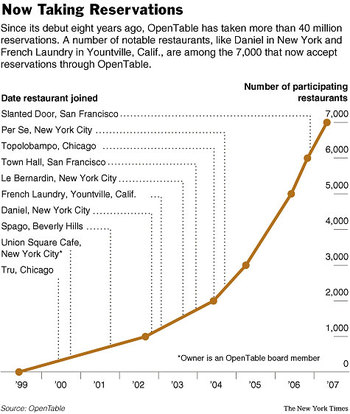

Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited below.