Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited below.

Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited below.

(p. C1) Jeffrey Taft is a road warrior in the global high-technology services economy, and his work shows why there are limits to the number of skilled jobs that can be shipped abroad in the Internet age.

Each Monday, Mr. Taft awakes before dawn at his home in Canonsburg, Pa., heads for the Pittsburgh airport and flies to Houston for the week.

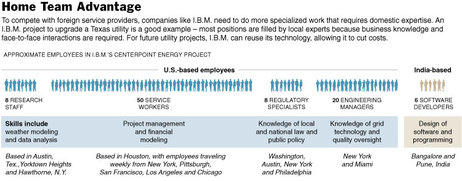

He is one of dozens of I.B.M. services employees from around the country who are working with a Texas utility, CenterPoint Energy, to install computerized electric meters, sensors and software in a “smart grid” project to improve service and conserve energy.

Mr. Taft, 51, is an engineer fluent in programming languages and experienced in the utility business. Much of his work, he says, involves being a translator between the different vernaculars and cultures of computing and electric power, as he oversees the design and building of software tailored for utilities. “It takes a tremendous amount of face-to-face work,” he said.

What he does, in short, cannot be done overseas. But some of the programming work can be, so I.B.M. employees in India are also on the utility project team.

The trick for companies like I.B.M. is to figure out what work to do where, and, more important, to keep bringing in the kind of higher-end work that needs to be done in this country, competing on the basis of specialized expertise and not on price alone.

The debate continues over how much skilled work in the vast service sector of the American economy can migrate offshore to lower-cost nations like India. Estimates of the number of services jobs potentially at (p. C4) risk, by economists and research organizations, range widely from a few million to more than 40 million, which is about a third of total employment in services.

Jobs in technology services may be particularly vulnerable because computer programming can be described in math-based rules that are then sent over the Internet to anywhere there are skilled workers. Already, a significant amount of basic computer programming work has gone offshore to fast-growing Indian outsourcing companies like Infosys, Wipro and Tata Consultancy Services.

To compete, companies like I.B.M. have to move up the economic ladder to do more complicated work, as do entire Western economies and individual workers. “Once you start moving up the occupational chains, the work is not as rules-based,” said Frank Levy, a labor economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “People are doing more custom work that varies case by case.”

In the field of technology services, Mr. Levy said, the essential skill is “often a lot more about business knowledge than it is about software technology — and it’s a lot harder to ship that kind of work overseas.”

For the full story, see:

Levy has co-authored a book that is relevant to the example and issues raised in the article. See:

Levy, Frank, and Richard J. Murnane. The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Creating the Next Job Market. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

IBM engineer Jeffrey Taft (blue shirt) has "local" knowledge of the connection between computer programming and the electric utility business. Here he is on-site in Houston at the offices of CenterPoint Energy. Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited above.

IBM engineer Jeffrey Taft (blue shirt) has "local" knowledge of the connection between computer programming and the electric utility business. Here he is on-site in Houston at the offices of CenterPoint Energy. Source of graphic: online verion of the NYT article cited above.