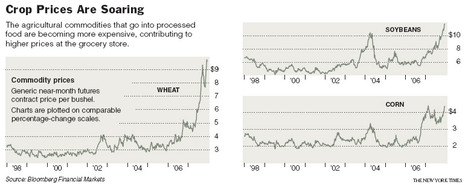

Source of graphs: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphs: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C1) Shopping at a Whole Foods Market in suburban Chicago, Meredith Estes said food prices have jumped so much she has resorted to coupons. Charles T. Rodgers Jr., an Arkansas cattle rancher, said normal feed rations so expensive and scarce he is scrambling for alternatives. In Oregon, Jack Joyce, the owner of Rogue Ales, said the cost of barley malt has soared 88 percent this year.

For years, cheap food and feed were taken for granted in the United States.

But now the price of some foods is rising sharply, and from the corridors of Washington to the aisles of neighborhood supermarkets, a blame alert is under way.

Among the favorite targets is ethanol, especially for food manufacturers and livestock farmers who seethe at government mandates for ethanol production. The ethanol boom, they contend, is raising corn prices, driving up the cost of producing dairy products and meat, and causing farmers to plant so much corn as to crowd out other crops.

The results are working their way through the marketplace, in this view, with overall consumer grocery costs up roughly 5 percent in a year and feed costs up more than 20 percent.

Now, with Congress poised to adopt a new mandate that would double the volume of ethanol made from corn, ethanol skeptics say a fateful moment has arrived, with the nation about to commit itself to decades of competition between food and fuel for the use (p. C4) of agricultural land.

(p. C4) “This is like a runaway freight train,” said Scott Faber, a lobbyist for the Grocery Manufacturers Association, who complained that ethanol has the same “magical effect” on politicians as the tooth fairy and Santa Claus have on children. “It’s great news for corn farmers, but terrible news for consumers.”

. . .

The price increases for corn have had a broad impact, both because farmers are planting more corn and less of other crops and because livestock producers are scrambling for feed substitutes. For instance, soybeans acreage planted this year was about 16 percent less than in 2006.

Feed costs have increased 25 to 30 percent in the last year, according to David Fairfield, director of feed services at the National Grain and Feed Association. He attributed virtually all of the increase to the demands of the ethanol industry

One consequence of the higher feed costs is rising competition for malt barley between livestock farmers, who want it for feed, and brewers, who need it for beer. Mr. Joyce, the Rogue Ales owner in Newport, Ore., said he has been forced to raise prices to pay for the additional costs of ingredients.

Mr. Rodgers, the Rison, Ark., rancher, said he used to feed his cattle a mixture of corn gluten and soybean hulls. But he said he cannot get corn gluten anymore, and the cost of soybean hulls has risen to $150 a ton from about $105 a ton.

For the full story, see:

ANDREW MARTIN. “The Price of Growing Fuel.” The New York Times (Tues., December 18, 2007): C1 & C4.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

“Jack Joyce, the owner of Rogue Ales in Newport, Ore., says the cost of barley has skyrocketed, forcing him to raise prices.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“Jack Joyce, the owner of Rogue Ales in Newport, Ore., says the cost of barley has skyrocketed, forcing him to raise prices.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

How can we be certain that these dismal consequences are ‘unintended’?

How can we be certain that these dismal consequences are ‘unintended’?