Source of photo: screen capture from slide show on online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

Source of photo: screen capture from slide show on online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C1) Part David Attenborough, part Indiana Jones, Mr. Kilham, an ethnobotanist from Massachusetts who calls himself the Medicine Hunter, has scoured remote jungles and highlands for three decades for plants, oils and extracts that can heal. He has eaten bees and scorpions in China, fired blow guns with Amazonian natives, and learned traditional war dances from Pacific Islanders.

But behind the colorful tales lies the prospect of money, lots of money — for Western pharmaceutical companies, impoverished indigenous tribes and Mr. Kilham.

. . .

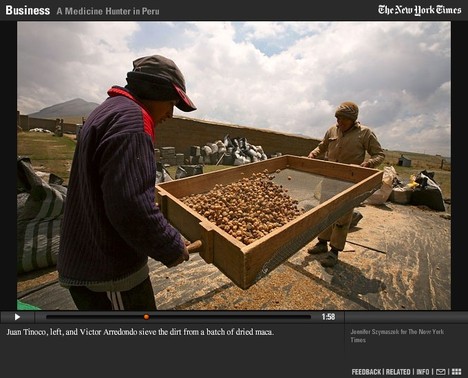

(p. C5) In Peru, Mr. Kilham is betting on maca, a small root vegetable that grows here in the central highlands — “a turnip that packs a punch,” he says, adding “it imparts energy, sex drive and stamina like nothing else.”

That view is supported by studies carried out at the International Potato Center, a Lima-based research center that is internationally financed and staffed. Studies there show maca improves stamina, reduces the risk of prostate cancer and increases the motility, volume and quality of sperm.

Some peer reviewed studies published in the journal Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology backed up those findings.

. . .

One product, Maca Stimulant, is sold in Wal-Mart under Mr. Kilham’s Medicine Hunter brand. Mr. Kilham earns a retainer from both Naturex and Enzymatic Therapy, in addition to royalties from another Medicine Hunter-branded product at Wal-Mart.

Mr. Kilham says he earns around $200,000 each year in retainers, and sales are so buoyant he expects to make “in the mid-six figures” in royalties next year.

Mr. Kilham insists he is not in the business simply for financial gain. His motivation comes from promoting herbal medicines and helping traditional communities, he said.

“I have financial security and don’t need to make money from this,” he said. “I believe trade is the best way to get good medicines to the public, to help the environment and to help indigenous people.”

He and Mr. Cam pay growers here in Ninacaca a premium of 6 soles (about $2) for a kilo of maca, almost twice the going rate of 3 to 3.40 soles a kilo. They have set up a computer room at the Chakarunas warehouse and a free dental clinic, the town’s first.

Mr. Kilham is clearly adored by the locals in these desolate, wind-swept villages. On a recent visit here, shamans, maca growers and their families flocked to him. Since only maca and potatoes grow at this altitude, they are thankful Mr. Kilham is helping them sell their produce.

For the full story, see:

ANDREW DOWNIE. “On a Remote Path to Cures.” The New York Times (Tues., January 1, 2008): C1 & C5.

(Note: ellipses added.)

Source of photo: screen capture from slide show on online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of photo: screen capture from slide show on online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.