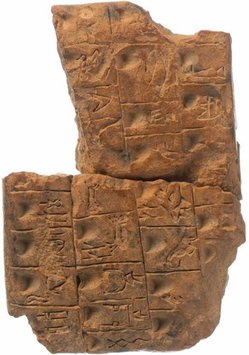

“A Sumerian clay tablet from around 3200 B.C. is inscribed in wedgelike cuneiform with a list of professions.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C5) CHICAGO — One of the stars of the Oriental Institute’s new show, “Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond,” is a clay tablet that dates from around 3200 B.C. On it, written in cuneiform, the script language of ancient Sumer in Mesopotamia, is a list of professions, described in small, repetitive impressed characters that look more like wedge-shape footprints than what we recognize as writing.

In fact “it is among the earliest examples of writings that we know of so far,” according to the institute’s director, Gil J. Stein, and it provides insights into the life of one of the world’s oldest cultures.

The new exhibition by the institute, part of the University of Chicago, is the first in the United States in 26 years to focus on comparative writing. It relies on advances in archaeologists’ knowledge to shed new light on the invention of scripted language and its subsequent evolution.

The show demonstrates that, contrary to the long-held belief that writing spread from east to west, Sumerian cuneiform and its derivatives and Egyptian hieroglyphics evolved separately from each another. And those writing systems were but two of the ancient forms of writing that evolved independently. Over a span of two millenniums, two other powerful civilizations — the Chinese and Mayans — also identified and met a need for written communication. Writing came to China as early as around 1200 B.C. and to the Maya in Mesoamerica long before A.D. 500.

. . .

The Oriental Institute, which opened in 1919, was heavily financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had been greatly influenced by James Henry Breasted, a passionate archaeologist.

. . .

Experts are still struggling to understand just how writing evolved, but one theory, laid out at the Oriental Institute’s exhibition, places the final prewriting stage at 3400 B.C., when the Sumerians first began using small clay envelopes like the ones in the show. Some of the envelopes had tiny clay balls sealed within. Archaeologists theorize that they were sent along with goods being delivered; recipients would open them and ensure that the number of receivables matched the number of clay tokens. The tokens, examples of which are also are in the show , transmitted information, a key function of writing.

For the full story, see:

GERALDINE FABRIKANT. “Hunting for the Dawn of Writing, When Prehistory Became History.” The New York Times (Weds., October 20, 2010): C5.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article is dated October 19, 2010.)