Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

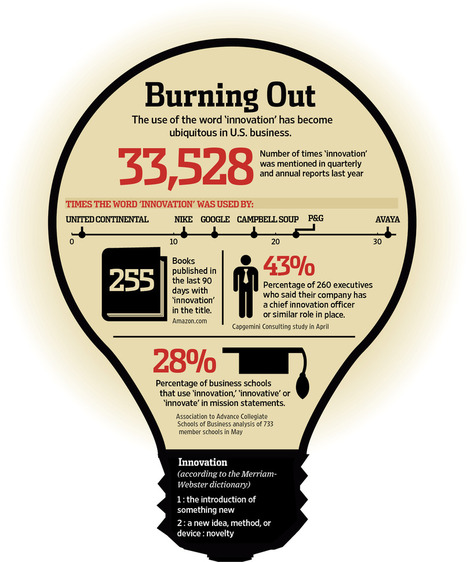

(p. B1) “Most companies say they’re innovative in the hope they can somehow con investors into thinking there is growth when there isn’t,” says Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School and the author of the 1997 book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma.”

. . .

Scott Berkun, the author of the 2007 book “The Myths of Innovation,” which warns about the dilution of the word, says that what most people call an innovation is usually just a “very good product.”

He prefers to reserve the word for civilization-changing inventions like electricity, the printing press and the telephone–and, more recently, perhaps the iPhone.

. . .

Mr. Berkun tracks innovation’s popularity as a buzzword back to the 1990s, amid the dot-com bubble and the release of James M. Utterback’s “Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation” and Mr. Christensen’s “Dilemma.”

. . .

(p. B8) Mr. Christensen classifies innovations into three types: efficiency innovations, which produce the same product more cheaply, such as automating credit checks; sustaining innovations, which turn good products into better ones, such as the hybrid car; and disruptive innovations, which transform expensive, complex products into affordable, simple ones, such as the shift from mainframe to personal computers.

A company’s biggest potential for growth lies in disruptive innovation, he says, noting that the other types could just as well be called ordinary progress and normally don’t create more jobs or business.

But the disruptive innovations can take five to eight years to bear fruit, he says, so companies lose patience.

It is far easier, he adds, for companies to just say they’re innovating. “Everybody’s innovating, because any change is innovation.”

For the full story, see:

LESLIE KWOH. “You Call That Innovation? Companies Love to Say They Innovate, but the Term Has Begun to Lose Meaning.” The Wall Street Journal (Weds., May 23, 2012): B1 & B8.

(Note: ellipses added.)