Even just the plausible possibility of a government veto of an acquisition, can stop the acquisition from happening. The feds thereby kill efficiency and innovation enhancing reconfigurations of assets and business units.

(p. 234) . . . , an opportunity arose that Google’s leaders felt compelled to consider: Skype was available. It was a onetime chance to grab hundreds of millions of Internet voice customers, merging them with Google Voice to create an instant powerhouse. Wesley Chan believed that this was a bad move. Skype relied on a technology called peer to peer, which moved information cheaply and quickly through a decentralized network that emerged through the connections of users. But Google didn’t need that system because it had its own efficient infrastruc-(p. 235)ture. In addition, there was a question whether eBay, the owner of Skype, had claim to all the patents to the underlying technology, so it was unclear what rights Google would have as it tried to embellish and improve the peer-to-peer protocols. Finally, before Google could take possession, the U.S. government might stall the deal for months, maybe even two years, before approving it. “We would have paid all this money, but the value would go away and then we’d be stuck with a piece of shit,” says Chan.

Source:

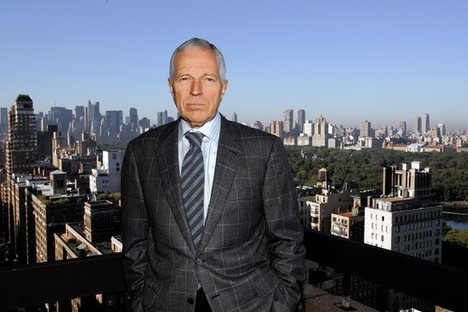

Levy, Steven. In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

(Note: ellipsis added.)