Recently I highlighted hedge fund philanthropist Lance Laifer’s efforts to fight malaria in Africa. Here is a letter-to-the-editor of the Wall Street Journal, in which a distinguished physician strongly endorses Laifer’s advocacy of the use of DDT against malaria:

Impoverished Africans should be grateful to philanthropist Lance Laifer for his effective outreach to reduce the tragic, needless toll of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa ("Malaria’s Toll" by Jason Riley, editorial page, Aug. 21). For his attempt to focus complacent Americans, Mr. Riley also deserves thanks — such clarity is obviously desperately needed, as even with all the publicity accorded to the ravages of malaria, someone as educated and intelligent as Mr. Laifer remained blithely unaware of this scourge until last year.

Both Mr. Laifer and Mr. Riley note the lack of attention given by official organizations to the more widespread use of DDT as a malaria control method, despite its long and honorable history for this use. Even with his money and other resources, Mr. Laifer has been unable to persuade Africans to utilize DDT. African exporters legitimately fear economic repercussions from wealthy Western trading partners, who continue to demonize this lifesaving insecticide despite the lack of evidence of DDT’s adverse health effects in humans.

And where is the Gates Foundation’s massive resources in this ongoing struggle to save a half-billion from sickness and millions from death? This organization asserts its devotion to reducing the toll of TB, AIDS and malaria — yet none of its funding is aimed toward the cheapest and most effective way to deal with malaria: increased indoor spraying with DDT. Maybe Warren Buffett can persuade his friends Bill and Melinda to target their contributions where they will do the most good, in the shortest time, for the most people. Malaria vaccines are many years away — DDT works in weeks or months.

Gilbert Ross M.D.

Executive and Medical Director

American Council on Science and Health

New York

For the source of the letter, and for other letters, see:

"Malaria Kills Millions — We Have the Cure." Wall Street Journal (Mon., August 28, 2006): A13.

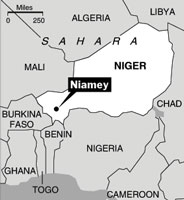

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Connecticut hedge-fund trader, and malaria-fighting activist and philanthropist. Source of image: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Source of book image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Source of book image: online version of WSJ article cited below.

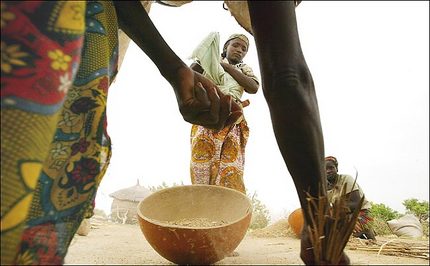

Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.