The refuse from homes demolished by the Abuja city government as part of their master plan. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

The refuse from homes demolished by the Abuja city government as part of their master plan. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

The story below, alas, is not an isolated example. The lessons from Hernando de Soto’s The Other Path, have still not been learned.

“They don’t want to see the common man, the poor man,” said Comrade Daniel, a motorcycle taxi driver, standing in the rubble of his neighborhood. He lost first his home and then his livelihood to a recent campaign to rid this stately capital of the blemishes of poverty. “They only care for themselves,” he said.

Mr. Daniel and others who live on the unruly edge of this tidy city in the mossy hills of central Nigeria say that Abuja has declared war on its poorest citizens.

. . .

. . . the city’s master plan was ignored for years by corrupt officials who allowed illegal neighborhoods to blossom, unauthorized street markets to spread and torpedo-like motorcycle taxis, called okada, often driven by illiterate young men, to choke the streets.

Much of that expansion was sanctioned — or at least overlooked — by the rulers of the day, and deeds were obtained by many of those who have lost their homes in the recent cleanup. Mr. Daniel, the motorcycle taxi driver, had a deed to his land, having paid about $160 for a small plot.

In 2003, a new minister was appointed to run the capital, and he declared his intention to hew strictly to the old master plan. Many political leaders cheered the decision, fretting that Abuja, built at enormous expense as an antidote to Lagos, was headed to the same chaotic fate.

But the declaration effectively rendered much of the daily life of millions of people illegal. As with most Africans, Nigerians deal mostly in the informal economy, the vast, unregulated, untaxed network that emerges, through the inexorable logic of the marketplace, to fill vital needs left unmet by government and the formal economy.

. . .

The master plan’s housing estates unfurl with the orderliness of a planned subdivision: town houses and apartments for the well heeled, tract homes and villas for the even better heeled. But there is little provision for the army of civil servants, whose low wages place the graceful homes of Abuja out of reach.

As for the maids, drivers, security guards and laborers without whom this city would cease to function — people like Mr. Daniel and his sister — there is no place for them at all. Many have moved farther still, commuting for hours from neighboring states to escape the bulldozers.

The government has said it plans to help resettle those displaced by the demolition, estimated to be in the tens of thousands, but those who have lost their homes say no one has offered them any compensation or a new place to live. And so they are left with the bitter knowledge that their capital has no place for them.

With their home reduced to rubble, Vashti and Comrade Daniel have moved into the back room of a cousin’s house. The house they lost was not some tin shack, but a proper house of bricks and mortar. Mr. Daniel’s income has been slashed by two-thirds by the ban on okada, and he does not know how he will rebuild.

“They say they want to make Abuja like London, but London wasn’t built in a day,” he said. “Once upon a time they had poor people in London, but they developed themselves. We just want that chance.”

For the full story, see:

LYDIA POLGREEN. "ABUJA JOURNAL; In a Dream City, a Nightmare for the Common Man." The New York Times (Weds., December 13, 2006): A4.

(Note: ellipses added.)

The reference to de Soto’s book is:

Soto, Hernando de. The Other Path. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

"Okada" are the motorcycle taxis that the city government of Abuja is trying to ban. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

"Okada" are the motorcycle taxis that the city government of Abuja is trying to ban. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Screen capture from CNN report "A Ruined Land," broadcast on December 19, 2006.

Screen capture from CNN report "A Ruined Land," broadcast on December 19, 2006.  Rats for dinner in Zimbabwe. Source: online CNN article cited above.

Rats for dinner in Zimbabwe. Source: online CNN article cited above.

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

William B. Dunavant, Jr. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

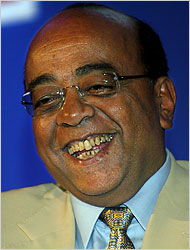

Source of map: online version of the NYT article cited above. Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Billionaire entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim. Source of photo: online version of the NYT article cited below.  Nicholas D. Kristof. Source of image: online verison of the NYT commentary cited below.

Nicholas D. Kristof. Source of image: online verison of the NYT commentary cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.