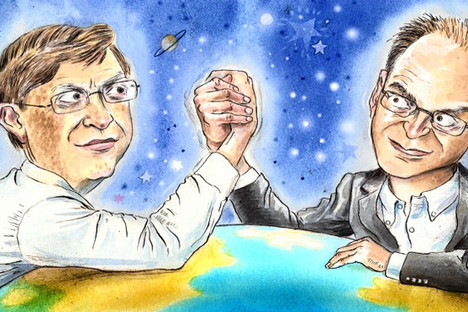

Alex on left, Irene Pepperberg on right. Source of photo: online version of the NYT review quoted and cited below.

Alex on left, Irene Pepperberg on right. Source of photo: online version of the NYT review quoted and cited below.

(p. 8) “Alex & Me,” Irene Pepperberg’s memoir of her 30-year scientific collaboration with an African gray parrot, was written for the legions of Alex’s fans, the (probably) millions whose lives he and she touched with their groundbreaking work on nonhuman communication.

. . .

Alex, . . . , is a delight — a one-pound, three-dimensional force of nature. Mischievous and cocky, he also gets bored and frustrated. (And who wouldn’t, when asked to repeat tasks 60 times to ensure statistical significance?) He shouts out correct answers when his colleagues (other birds) fail to produce them. If Pepperberg inadvertently greets another bird first in the morning, Alex sulks all day and refuses to cooperate. He demands food, toys, showers, a transfer to his gym.

This ornery reviewer tried to resist Alex’s charms on principle (the principle that says any author who keeps telling us how remarkable her subject is cannot possibly be right). But his achievements got the better of me. During one training session, Alex repeatedly asked for a nut, a request that Pepperberg refused (work comes first). Finally, Alex looked at her and said, slowly, “Want a nut. Nnn . . . uh . . . tuh.”

“I was stunned,” Pepperberg writes. “It was as if he were saying, ‘Hey, stupid, do I have to spell it out for you?’ ” Alex had leaped from phonemes to sound out a complete word — a major leap in cognitive processing. Perching near a harried accountant, Alex asks over and over if she wants a nut, wants corn, wants water. Frustrated by the noes, he asks, “Well, what do you want?” Mimicry? Maybe. Still, it made me laugh.

After performing major surgery on Alex, a doctor hands him, wrapped in a towel, to an overwrought Pepperberg. Alex “opened an eye, blinked, and said in a tremulous voice, ‘Wanna go back.’ ” It’s a phrase Alex routinely used to mean “I’m done with this, take me back to my cage.” The scene is both wrenching — Alex had been near death — and creepy, evoking the talking bundle in “Eraserhead.”

Pepperberg frames her story with Alex’s death: the sudden shock of it, and the emotional abyss into which she fell. Ever the scientist, she wonders why she felt so strongly. The answer she comes up with is both simple — her friend was dead — and complex. At long last, and buoyed by the outpouring of support from people around the world, she could express the emotions she’d kept in check for 30 years, the better to convince the scientific establishment that she was a serious researcher generating valid and groundbreaking data (some had called her claims about animal minds “vacuous”). When Alex died, that weight lifted.

For the full review, see:

ELIZABETH ROYTE. “The Caged Bird Speaks.” The New York Times Book Review (Sun., November 9, 2008): 8.

(Note: first two ellipses added; last two in original.)

(Note: the online version of the review has the date November 7, 2010.)

(p. A21) Even up through last week, Alex was working with Dr. Pepperberg on compound words and hard-to-pronounce words. As she put him into his cage for the night last Thursday, she recalled, Alex looked at her and said: “You be good, see you tomorrow. I love you.”

He was found dead in his cage the next morning, Dr. Pepperberg said.

For the full obituary, see:

BENEDICT CAREY. “Brainy Parrot Dies, Emotive to the End.” The New York Times (Tues., September 11, 2007): A23.

A reporter questions Oxford professor Alex Kacelnik:

I asked him why more researchers weren’t working with African grays, trying to replicate Pepperberg’s achievements with Alex. “The problem with these animals is that they are the opposite of fruit flies,” he said, meaning that parrots live a long time–often, fifty to sixty years in captivity. “Alex was still learning when he died, and he was thirty.” He later elaborated: “Irene’s work could not really have been planned ahead, as nobody knew what was possible. . . . Alex’s development as a unique animal accompanied Irene’s as a unique scientist. Hers is not a career trajectory one would advise to young scientists–it’s too risky.”

For the full story, see:

Margaret Talbot. “Birdbrain.” The New Yorker (May 12, 2008).

(Note: ellipsis in original.)

The book on Alex by Pepperberg, is:

Pepperberg, Irene M. Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Uncovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence–and Formed a Deep Bond in the Process. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2008.