(p. A13) Biofuels are under siege from critics who say they crowd out food production. Now these fuels made from grass and grain, long touted as green, are being criticized as bad for the planet.

At issue is whether oil alternatives — such as ethanol distilled from corn and fuels made from inedible stuff like switch grass — actually make global warming worse through their indirect impact on land use around the world.

For example, if farmers in Brazil burn and clear more rainforest to grow food because farmers in the U.S. are using their land to grow grain for fuel, that could mean a net increase in emissions of carbon dioxide, the main “greenhouse gas” linked to climate change.

. . .

A study published in February [2008] in the journal Science found that U.S. production of corn-based ethanol increases emissions by 93%, compared with using gasoline, when expected world-wide land-use changes are taken into account. Applying the same methodology to biofuels made from switch grass grown on soil diverted from raising corn, the study found that greenhouse-gas emissions would rise by 50%.

Previous studies have found that substituting biofuels for gasoline reduces greenhouse gases. Those studies generally didn’t account for the carbon emissions that occur as farmers world-wide respond to higher food prices and convert forest and grassland to cropland.

For the full story, see:

STEPHEN POWER. “If a Tree Falls in the Forest, Are Biofuels To Blame? It’s Not Easy Being Green.” The Wall Street Journal (Tues., November 11, 2008): A13.

(Note: ellipsis, and bracketed year, added.)

Two relevant articles appeared in Science in the Feb. 29, 2008 issue:

Fargione, Joseph, Jason Hill, David Tilman, Stephen Polasky, and Peter Hawthorne. “Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt.” Science 319, no. 5867 (Feb. 29, 2008): 1235-38.

Searchinger, Timothy, Ralph Heimlich, R. A. Houghton, Fengxia Dong, Amani Elobeid, Jacinto Fabiosa, Simla Tokgoz, Dermot Hayes, and Tun-Hsiang Yu. “Use of U.S. Croplands for Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gases through Emissions from Land-Use Change.” Science 319, no. 5867 (Feb. 29, 2008): 1238-40.

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Source of the map: online version of the NYT article cited above.  Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

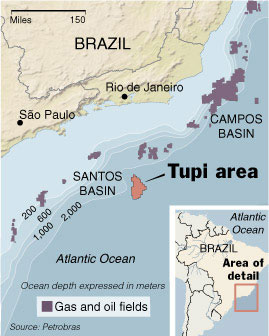

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.