"Emily Prager at her lane house in Shanghai." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

"Emily Prager at her lane house in Shanghai." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

The centers of dynamism are not set in stone. I once asked the philosopher Alan Donagan why the Scottish enlightenment had occurred where (Edinburgh) and when (in the mid-late 18th century) it did. With his usual good humor he told me that I was asking a bad question–that my question assumed that enlightenments were determined. He instead believed that they were chance occurrences resulting from the free-will choices of individuals.

I think that there was something to what he said. But I also believe that some institutions, and some policies of government, can greatly increase the probability that fruitful dynamism will occur. For instance, free markets tend to tolerate diversity and experimentation, and to reward initiative.

In the past, locations of economic dynamism, also were often locations of intellectual dynamism. I wonder if the connection is still true today, and if not, why not?

Among past centers of dynamism were Miletus, Athens, Florence, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, and New York City. Today, centers of economic dynamism include Las Vegas, Dubai and Shanghai. The article quoted below paints a generally appealing picture of Shanghai.

(p. D1) I decided to move myself and my 12-year-old daughter, Lulu — whom I had adopted as a baby in China — from the old capital of the world to the new: to make a home in Shanghai, a city of the future.

I knew something about Shanghai, having been here on trips several times in the last few years. The city was always so excited it could hardly contain itself. It is a microcosm of the Asian boom, stuffed with people giddy on hope and thrilled to be changing. It recalls the greatness of New York in the early ’70s, except for one thing: Like the rest of China, Shanghai was largely closed to the outside world, and real economic growth, for nearly 50 years after World War II. It is a place where every car on the road is brand new and every pet recently acquired, but the person you just met might trace his family back 70 generations. The modernity and polish that Manhattan learned between 1945 and 1995, Shanghai is cramming for as fast as it can, and it’s fascinating to watch.

. . .

(p. D6) Pets are new to Chinese people and they don’t know very much about them. Dogs are not neutered and they are walked without leashes. Many people are terrified of dogs, particularly given the country’s serious rabies problem.

Twice when I was walking Skippy, young women caught sight of him and screamed in terror at the top of their lungs. Because having a pet is so new, there is a video showing how to pick up after a dog and wash his paws after his walk, which appears many times a day on a huge video screen on Huaihai, the city’s other main shopping street.

For the full story, see:

EMILY PRAGER. "At Home Abroad; Settling Down in a City in Motion." The New York Times (Thurs., July 19, 2007): D1 & D6.

(Note: ellipsis added.)

"On the streets of Shanghai, the author’s injured foot attracts less attention than her pet dog, still a rare sight in the city." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

"On the streets of Shanghai, the author’s injured foot attracts less attention than her pet dog, still a rare sight in the city." Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

Source of table: "World Publics Welcome Global Trade — But Not Immigration." Pew Global Attitudes Project, a project of the PewResearchCenter. Released: 10.04.07 dowloaded from:

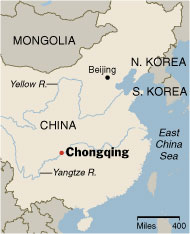

On left, Wu Ping, with her tall brother in the background. On right, a map showing the location of Chongqing in China. Source of photo and map: online version of the NYT article cited above.

On left, Wu Ping, with her tall brother in the background. On right, a map showing the location of Chongqing in China. Source of photo and map: online version of the NYT article cited above.