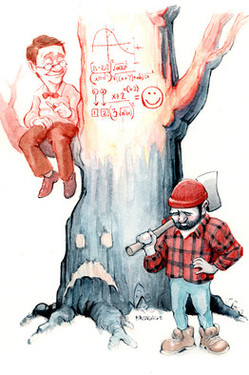

Bhidé makes thought-provoking comments about the role of the entrepreneurial or “venturesome” consumer in the process of innovation. The point is the mirror image on one made by Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy when he emphasized that consumer resistance to innovation is one of the obstacles that entrepreneurs in earlier periods had to overcome. (The decline of such consumer resistance was one of the reasons that Schumpeter speculated that the entrepreneur might become obsolete.)

I would like to see Bhidé’s evidence on his claim that technology rapidly advanced during the Great Depression. The claim seems at odds with Amity Shlaes’ claim that New Deal policies often discouraged entrepreneurship.

(p. A15) Consumers get no respect — we value thrift and deplore the spending that supposedly undermines the investment necessary for our long-run prosperity. In fact, the venturesomeness of consumers has nourished unimaginable advances in our standard of living and created invaluable human capital that is often ignored.

Economists regard the innovations that sustain long-run prosperity as a gift to consumers. Stanford University and Hoover Institution economist Paul Romer wrote in the “Concise Encyclopedia of Economics” in 2007: “In 1985, I paid a thousand dollars per million transistors for memory in my computer. In 2005, I paid less than ten dollars per million, and yet I did nothing to deserve or help pay for this windfall.”

In fact, Mr. Romer and innumerable consumers of transistor-based products such as personal computers have played a critical, “venturesome” role in generating their windfalls.

. . .

History suggests that Americans don’t shirk from venturesome consumption in hard times. The personal computer took off in the dark days of the early 1980s. I paid more than a fourth of my annual income to buy an IBM XT then — as did millions of others. Similarly, in spite of the Great Depression, the rapid increase in the use of new technologies made the 1930s a period of exceptional productivity growth. Today, sales of Apple’s iPhone continue to expand at double-digit rates. Low-income groups (in the $25,000 to $49,999 income segment) are showing the most rapid growth, with resourceful buyers using the latest models as their primary device for accessing the Internet.

Recessions will come and go, but unless we completely mess things up, we can count on our venturesome consumers to keep prosperity on its long, upward arc.

For the full commentary, see:

Amar Bhidé. “Consumers Can Still Spot Value in a Crisis.” Wall Street Journal (Thurs., MARCH 11, 2009): A15.

(Note: ellipsis added.)