When I was a student at Wabash College, Ben Rogge arranged for Liberty Fund to finance my attendance at a couple of weekend seminars at the Foundation for Economic Education in New York. The seminars were taught by Rogge, Edmund Opitz, and Leonard Read. I remember upon returning to Wabash after one of the seminars, Rogge asking me what I thought of Read. I said something along the lines that I didn’t much like his presentation style. I remember saying that he expressed himself in a way that I associated with used car salesmen. (So unlike Rogge’s low-key, witty, intensity.)

My memory is that Rogge did not respond directly to my comment, but (perhaps with a hint of a smile) mentioned that among many audiences, especially in business, Leonard Read was an extremely effective speaker.

I do not doubt that, and I also do not doubt that Read belongs in the pantheon of free market defenders. His essay "I, Pencil" is by itself sufficient for admission. But he did more than write and speak; he nurtured and called attention to others who had wisdom to offer. For one small example, many of us learned about Albert Jay Nock’s "The Remnant" through Leonard Read’s The Freeman.

I believe that the last time I saw Read was at the memorial service at Wabash College for Ben Rogge. I ended up sitting near Read and Opitz, who had flown in from New York. I introduced myself as a Rogge student who had attended FEE seminars.

I remember Read looking very sad, and depressed, and almost lost. I also remember that he expressed some mild indignation that more of Rogge’s students hadn’t made it back for the memorial service.

But as a serious reader of "The Remnant," Read on further reflection probably realized that the attendance at a memorial service is not a good measure of a teacher’s influence on his students.

Apparently one student, whom Read himself influenced, was Charles Koch:

(p. A8) Whereas the bookshelves of most of America’s leading CEOs are stocked with pop corporate management and "how to succeed" books, Mr. Koch’s office is a wall-to-wall shrine to writings in classical economics, or, as he calls it, "the science of liberty." The authors who have had the most profound influence on his own political philosophy include F.A. Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Joseph Schumpeter, Julian Simon, Paul Johnson and Charles Murray. Mr. Koch says that he experienced an intellectual epiphany in the early 1960s, when he attended a conference on free-market capitalism hosted by the late, great Leonard Read.

For the full commentary, see:

STEPHEN MOORE. "THE WEEKEND INTERVIEW with Charles Koch; Private Enterprise." The Wall Street Journal (Sat., May 6, 2006): A8.

(Note: In the quotation above, I have corrected the WSJ’s misspelling of Read’s last name.)

Charlie Munger. Sourge of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Charlie Munger. Sourge of image: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Alex Tabarrok. Source of image:

Alex Tabarrok. Source of image:

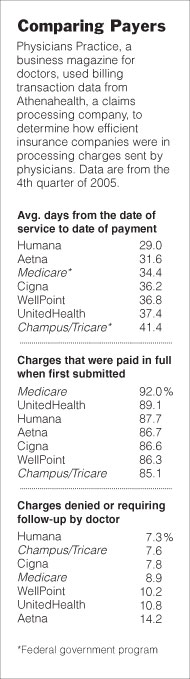

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of the WSJ article cited below. Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.

Source of the graphic: the online version of the NYT article cited below.