“Robert Deluce set up Porter Airlines at Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport in October 2006.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

“Robert Deluce set up Porter Airlines at Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport in October 2006.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited below.

Clayton Christensen explains why upstart entrepreneurs who move up-market to serve under-served customers, will almost always lose to motivated incumbents.

Apparently Robert Deluce has not read Christensen.

(p. B8) TORONTO–As a teenager, Robert Deluce learned to fly at this city’s small airport just outside the downtown on a Lake Ontario island.

Lately, the 59-year-old airline entrepreneur has been giving his own brand of flying lessons there in a dogfight with larger competitors over a lucrative flying niche: the high-margin business traveler.

n 2005, Mr. Deluce bought the airport’s ramshackle terminal and later kicked out an Air Canada regional partner named Jazz Air. Then, he set up Porter Airlines, which has become a hit with business fliers for its top-notch service and convenient location, a one-minute ferry ride from the downtown waterfront. Earlier this month, closely held Porter opened the first phase of a gleaming, 150,000-square-foot terminal that eventually will house two passenger lounges and 10 aircraft gates.

. . .

The new carrier’s mascot is a raccoon. “He’s mischievous and determined and pretty much always achieves his desired goal,” said Mr. Deluce, chuckling over breakfast at a Toronto hotel. “Air Canada and Jazz probably think he’s over-mischievous.”

. . .

In recent years, Toronto’s waterfront has been revitalized, with high-rise condos and parks replacing grain elevators and industrial warehouses. Air Canada’s partner Jazz and a predecessor, which had been flying to and from the downtown airport for years, reduced service even as the redevelopment was progressing. The airport’s traffic waned to 25,000 fliers in 2005 from 400,000 a year in the late 1980s.

Smelling opportunity, Mr. Deluce pounced, acquiring the old terminal and evicting Jazz. He raised C$126 million in start-up capital and placed a US$500 million order for 20 Canadian-built turboprop aircraft. With 70 seats, they are perfectly sized for the airport’s short, 4,000-foot runway. Porter took wing in October 2006.

His aggressive tactics as CEO have earned him both criticism and grudging respect. Brian Iler, chairman of CommunityAir, a Toronto citizens advocacy group that wants the airport shut because of noise issues and other concerns, gives Mr. Deluce his due. “Everything he has done, he’s managed to turn things his way,” Mr. Iler says. “It’s an amazing run of luck.”

. . .

Porter now flies to four U.S. destinations and seven other cities in Eastern Canada, with an eighth coming this month. It had its first month of profitability in June 2007 and paid out to its employee profit-sharing plan that year and in 2008, Mr. Deluce says. He won’t say whether Porter was profitable in 2009.

The new airline has attracted a following for its downtown location, competitive fares, leather seats with generous legroom and complimentary beer, wine and snacks. Female flight attendants wear retro pillbox hats and peplum jackets.

Christopher Sears, vice president of research for Montreal-based brokerage firm MacDougall, MacDougall & MacTier Inc., said he has flown Porter 30 to 40 times between Montreal and Toronto. Once he arrives in Toronto, he grabs a free shuttle to a hotel two blocks from his firm’s Toronto office.

“Porter has built up a lot of goodwill with me,” he says, vowing to stick with the company even if rivals break into the downtown airport.

For the full story, see

SUSAN CAREY. “Tiny Airline Flies Circles Around Its Rivals; Top-Notch Service, Proximity to Downtown Toronto Make Porter a Hit With High-Margin Business Travelers.” The Wall Street Journal (Weds., MARCH 17, 2010): B8.

(Note: ellipses added.)

(Note: the online version of the article has the slightly different title “Tiny Airline Flies Circles Around Rivals; Top-Notch Service, Proximity to Downtown Toronto Makes Porter a Hit With High-Margin Business Travelers.”)

On Christensen’s theories, see:

Christensen, Clayton M., and Michael E. Raynor. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

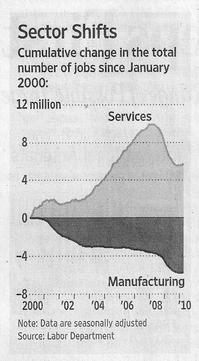

Source of graph: online version of the WSJ article quoted and cited above.