“Alicia Ledlie, senior director of health business development for Wal-Mart, said walk-in medical clinics would look like the mockup behind her, in a warehouse in Bentonville, Ark.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

“Alicia Ledlie, senior director of health business development for Wal-Mart, said walk-in medical clinics would look like the mockup behind her, in a warehouse in Bentonville, Ark.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited below.

(p. C4) Moving to upgrade its walk-in medical clinic business, Wal-Mart is set to announce on Thursday plans for several hundred new clinics at its stores, using a standardized format and jointly branded with hospitals and medical groups.

. . .

Walk-in medical clinics are a growing industry, with numerous competitors that include big-box retailers, drugstores and even grocery chains around the country. Industry executives say 1,500 to 1,800 clinics will be open by the end of the year.

Propelled by the drugstore chains CVS and Walgreens, by far the biggest sponsors of the clinics to date, more than 700 clinics have opened in the last 15 months. But the business model is unproven so far.

Few, if any, clinics are profitable, according to industry analysts, and only a handful have broken even on daily operations. Most have been open a year or less, and executives say it takes up to three years for a clinic to become profitable enough to recover start-up costs.

Medical societies are inclined to be skeptical of the clinics. The American Academy of Pediatrics opposes them, saying they add to fragmentation in the health care system.

Dr. Edward Zissman, a pediatrician in central Florida, said he had qualms about hospitals that hook up with the clinics. “Putting their name on a product that I don’t think has the highest quality,” he said, “is going to cost them dearly with physicians.”

The American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Medical Association have set forth principles for clinics to observe, including sending patients’ medical record to their doctors and finding doctors for patients who do not already have them. Most states require varying degrees of physician supervision of the clinic nurses. Clinic operators say they are complying.

Many patients have said they like the convenience of the walk-in clinics’ weekend and evening hours, the short waiting times to see a nurse practitioner, and the posted price lists for a limited menu of care like tests and prescriptions for sore throats and ear infections and seasonal flu shots.

. . .

“The clinics are the latest big example of how you could think about consumers and what their needs are, rather than a health care system exclusively designed around the needs of providers,” said Margaret Laws, director of an innovations program at the California Health Care Foundation, an independent group that finances health policy research.

For the full story, see:

MILT FREUDENHEIM. “Wal-Mart Will Expand In-Store Medical Clinics.” The New York Times (Thurs., February 7, 2008): C4.

(Note: ellipses added.)

“The design of the Wal-Mart medical clinic is intended to look like a doctor’s office, complete with the usual medical hardware.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

“The design of the Wal-Mart medical clinic is intended to look like a doctor’s office, complete with the usual medical hardware.” Source of caption and photo: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

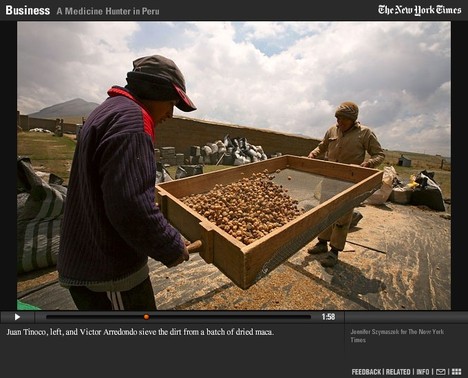

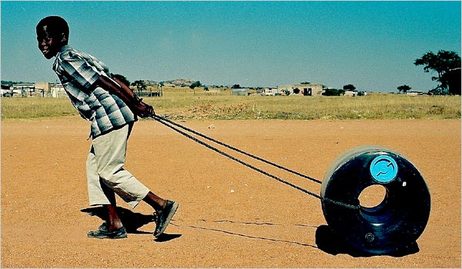

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.

The photo on the left shows a woman safely drinking bacteria-laden water through a filter. The photo on the right shows a "pot-in-pot cooler" that evaporates water from wet sand between the pots, in order to cool what is in the inner pot. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article quoted and cited above.