T.W. Schultz used to emphasize that the level of technology in an economy depended more on the incentives and institutions for adoption and diffusion, and less on the invention of the technology, which he thought was a shorter hurdle than usually thought. The Antikythera Mechanism is one historical technology that dramatically supports Schultz’s view. If it survives scrutiny, the following article would provide an additional example supporting Schultz.

(p. A18) Reporting the results of his study, Michel W. Barsoum, a professor of materials engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, concluded that the use of limestone concrete could explain in part how the Egyptians were able to complete such massive monuments, beginning around 2550 B.C. They used concrete blocks, he said, on the outer and inner casings and probably on the upper levels, where it would have been difficult to hoist carved stone.

”The sophistication and endurance of this ancient concrete technology is simply astounding,” Dr. Barsoum wrote in a report in the December issue of The Journal of the American Ceramic Society.

Dr. Barsoum and his co-workers, Adrish Ganguly of Drexel and Gilles Hug of the National Center for Scientific Research in France, analyzed the mineralogy of samples from several parts of the Khufu pyramid, and said they found mineral ratios that did not exist in any known limestone sources. From the geochemical mix of lime, sand and clay, they concluded, ”the simplest explanation” is that it was cast concrete.

For the full story, see:

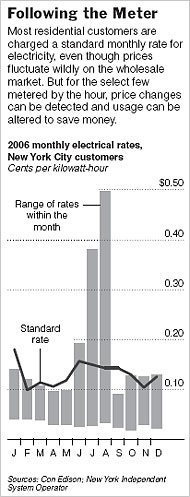

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above.

Graph showing the range of variation in hourly electricity rates in different months. Source of graphic: online version of the NYT article cited above. CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.

CEO of drug company Eli Lilly. Source of image: online version of WSJ artcle cited below.